An Artisanal Review of 2025

and thoughts for crafting 2026

I suspect that for many of us, this is the most important time of the year. A liminal space between the end of one year and the beginning of the next. A pause after the manic consumption our economy seems to require of Christmas, before we return to its equally manic demands for growth at any cost.

A space in which we can reflect on what we have done and what we might choose to do next. As 2025 ends and 2026 begins, that space feels unusually charged.

One of the novelties this year has been the ability to feed my writing back into itself and interrogate it using different AI tools. What was I thinking? What was I noticing? What kept recurring? It has proved a valuable exercise, partly because I do not write to a plan; I write from where I am and from what catches my attention, and this approach helps me to join dots.

Looking back, those dots clustered around four broad themes:

The first was a recurring interest in what does not change amid technological upheaval. The constants of human connection, such as meaning, trust, fairness and belonging. None of these is easily measurable, and all of them tend to slip from view when data and short term optimisation dominate our thinking. I found myself returning to the idea of artisans as those who weave the unchanging into the changing, attending to what technology struggles to see. That thread led me to questions of scale and multiplication, a distinction I will return to, particularly as scale makes organisations (and us) increasingly sterile when it comes to innovation and human flourishing.

The second cluster explored technology’s double-edged sword. I was interested in what happens when expanding technological capability collides with organisational structures designed for efficiency and productivity. Again and again, I noticed the same tension; technology enables new forms of work, but industrial age organisations often struggle to accommodate them. In response, they constrain rather than adapt. Over time, this raised an uncomfortable thought; many of the organisations we rely on are becoming counterproductive, not through malice or incompetence, but as management shifts from enabling the possible to guarding what has already been ritualised and sanctified.

The third followed a more personal line of inquiry. What does technology do to us as individuals? In performative cultures, it can emphasise what we are functionally, rather than who we are creatively. I became interested in the difference between technologies that hollow us out and those that amplify originality, and AI in particular began to feel like a kind of Tolkien’s “one ring”, binding us into mass mimicry by removing friction and difficulty, and in doing so quietly encouraging mediocrity at scale.

The fourth took me back to where I started, with people and with what does not change. In our obsession with data, we often fail to notice what goes missing. That took me towards the idea of artisans as strange attractors in the language of chaos theory. People who hold space for the conversations that data cannot have. I thought of artisans, heretics, pirates, and alchemists as boundary crossers, and as the year drew to a close, alchemy offered itself as a way to carry these ideas into 2026. That, in turn, led to the Athanor, the vessel in which alchemists conduct their work, and to the decision to create a separate space for those who wish to undertake the work of change, rather than simply observe it.

I suspect that when we look back, 2025 will prove to have been a pivotal year.

One of the gifts of this pause between years is the chance for a second distillation. Not only can we reflect on what we have noticed, but we can sit with others and ask what lies beneath it. Why are these things coming into view now? What might deserve our attention as we enter 2026?

Experience suggests that this focus need not be correct to be powerful. But we need to begin somewhere. To discover that we are moving in the wrong direction, we must first move.

Alan Kay famously said that the best way to predict the future is to invent it. It is a compelling line, but I am increasingly drawn to a different framing. Masahiro Morioka suggests that life is something we feel our way into rather than discover.

How we approach it shapes what it becomes.

Perhaps we have more choice than we think, if we approach it wisely.

So, as we enter 2026, I am choosing two things to focus on. First, AI as a form of personal transport. Second, the idea of scale as sterility.

AI as personal transport

Our media has an almost limitless appetite for anything that can be dressed up as a crisis or a revolution. I am amused and slightly bemused that we are currently being warned of a “cold weather bomb”, complete with colour coded alerts, when the reality is that it will simply be a bit chilly for a week or two. It’s what winter does. There is no news to it.

I think we are seeing something similar with AI. It is often framed as a revolution in its own right, when in truth it is part of a technological wave that has been unfolding since the 1970s. Carlota Perez offers a useful lens here. She shows that major technological breakthroughs follow long diffusion patterns that reshape not only the economy, but society itself. Each wave, of 50-60 years, brings a new common sense about organisation, institutions and best practice.

These revolutions tend to unfold in two phases. An installation period marked by experimentation, speculation and inequality, followed by a deployment period in which institutions slowly adapt, and benefits spread more broadly. Technology alone does not determine outcomes; social and institutional choices matter just as much, and I think this lag between technological possibility and organisational adaptation is where much of our current tension sits.

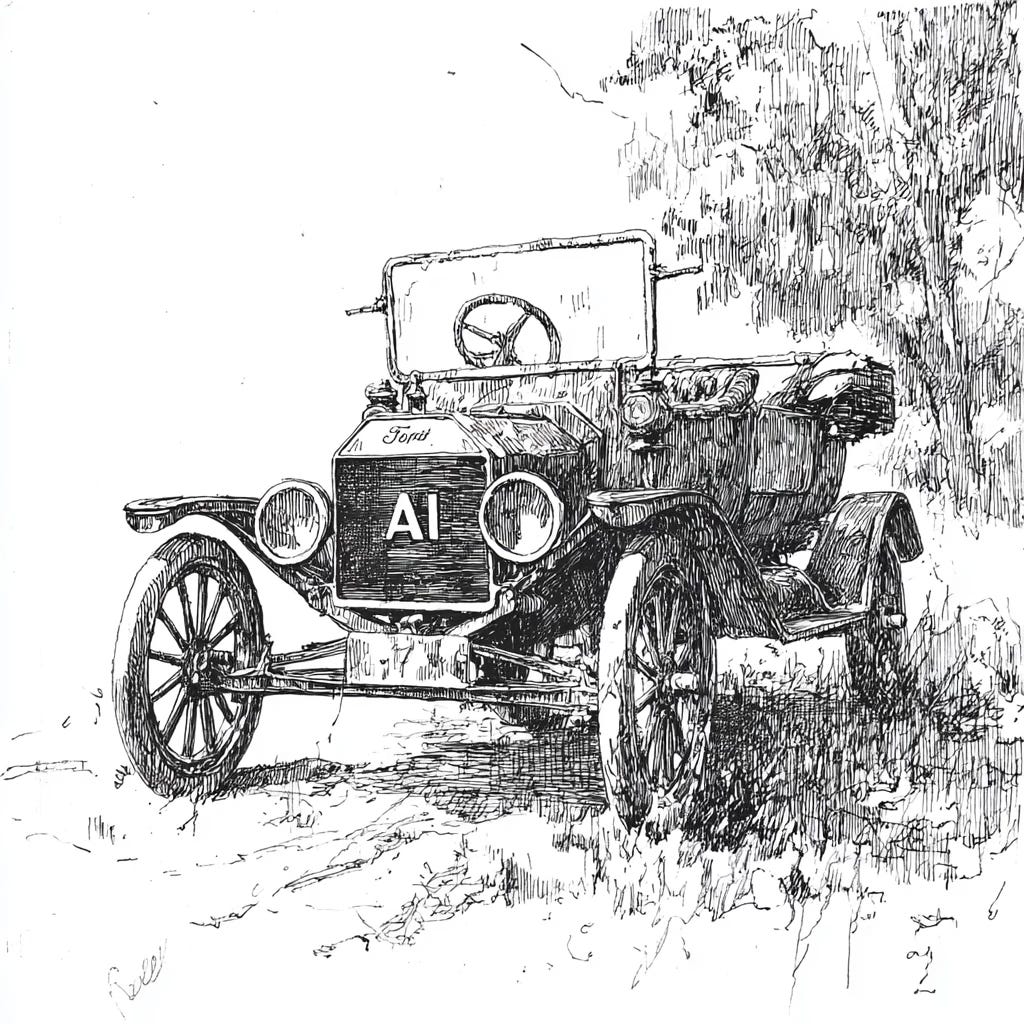

If we look back to the early twentieth century, technological change initially transformed society through industry, enabling mass transport by rail, road and air. Yet the most profound social shift occurred with the advent of the car. Henry Ford did not invent it, but he standardised it, simplified it, and built an infrastructure that ordinary people could learn from. He made cars accessible and understandable and in doing so, he made personal transport possible. People were no longer limited to following where institutions led. They could choose where to go themselves.

I wonder whether AI might be doing something similar. Before its recent advances, modelling, analysis and optimisation existed, but they largely lived inside firms, consultancies and governments that had the resources to support them. Today, capabilities once locked behind teams and budgets are accessible to individuals. The cost of experimentation has collapsed. Iteration now rewards curiosity more than hierarchy.

Railways centralised movement. Cars decentralised it. Enterprise AI centralises intelligence, but AI used well can decentralise it again.

There is an obvious caveat. Cars empowered drivers who learned to drive well, but tended to kill those who did not respect them. AI will not empower everyone. It will empower those who treat it as a craft, who develop judgement, taste and restraint, and who remain morally and intellectually in the loop. Those who don’t will end up as passengers, or victims.

This raises an awkward question for organisations. Just as railways did not vanish, organisations will not disappear; however, they may no longer be the only places where complex work can occur. Individuals with AI fluency may rival small teams, and small teams using AI may unseat large ones, because Capital is promiscuous. Coordination can increasingly happen through loose networks rather than rigid hierarchies. In some respects, this may look less like modern corporations and more like Guilds 2.0.

The risks are real. Cars brought freedom and sprawl, but also accidents and environmental damage. AI may expand agency, but it can also encourage cognitive overreach and moral externalities.

Developing horsepower is easy. Developing the skill to handle it is something else entirely.

The greatest challenge in all this is us. We are the inheritors of industrial systems in which survival depended on compliance, yet we now find ourselves in a world where that compliance increasingly leads to irrelevance.

The Industrial Revolution provided mass transport for organisations before it enabled mobility for individuals. AI may reverse that pattern, offering mass capability to individuals before organisations fully learn how to respond.

Agency may an attractive idea, but it carries responsibility, and responsibility can be uncomfortable. We are accountable, perhaps more than for a very long time, for our own futures.

This will be my starting theme for 2026. AI may be the most significant personal enabler we have ever encountered. Working with it will be a craft. Developing that craft will not be straightforward, and the challenges are already with us.

The organisations we have are not there for our benefit.

What might we do instead?

Scale as Sterility

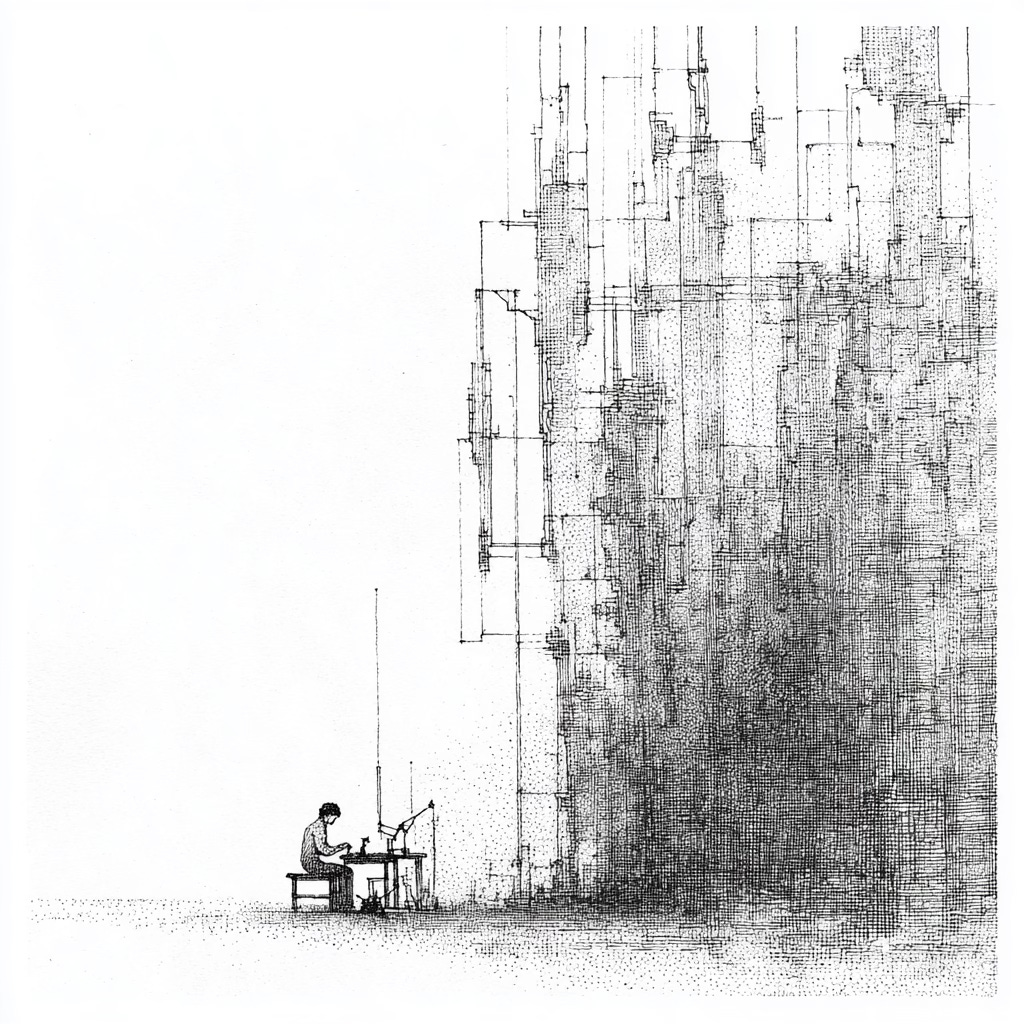

If AI reintroduces personal agency, it also casts existing working environments in a harsher light. It raises a simple but unsettling question. If the tools are now capable and experimentation is cheaper than ever, why does so much organised work still feel so flat? I do not think this is a failure of imagination or intent. It is structural. Scale entails a hidden bargain.

Large systems exist because they work. They deliver efficiency, predictability and productivity at levels smaller systems cannot. They reduce cost per unit, smooth variation and enable complex coordination. Modern life depends on these achievements.

But scale also changes what systems reward. As organisations grow, they become increasingly sensitive to risk. Errors travel further. Failure becomes reputational rather than local. Small deviations can have disproportionate consequences. Over time, systems adapt by valuing repeatability over originality, compliance over judgement, and safety over surprise.

This is not stupidity. It is self defence.

The consequence is that optimisation quietly displaces vitality. Variation becomes noise, and anomalies become threats. Experimentation must justify itself in advance, and innovation narrows into safe recombinations of the familiar. Franchises replace exploration, until what remains is competence without aliveness and motion without direction. A kind of professional sterility, with our Animal Spirits caged and tamed.

At the human scale, judgment is personal, and accountability is immediate. Trust lives in relationships rather than processes. At the organisational scale, these qualities have to be abstracted. Rules replace norms. protocols replace judgement and roles replace people. It is not a moral failure, it is a cognitive necessity.

But abstraction has a cost. When judgement is externalised into process, people are trusted less to think and more to comply, and when responsibility is diffused through systems, ownership weakens.

When success is defined narrowly by metrics, everything else fades from view.

This is how sterility feels from the inside. Not like oppression, but like thinning. A quiet sense that something important has gone missing, even as performance improves.

There is a deeper inversion at work. Systems designed to support human flourishing can, beyond a certain point, begin to undermine it. Tools that once extended agency start to prescribe behaviour. Success overshoots its purpose. More process reduces judgement, more optimisation reduces imagination, and more safety reduces aliveness.

Seen this way, sterility is not a bug. It is a feature of success taken too far.

AI does not create this condition; it reveals it. By collapsing the cost of experimentation and shifting capability from hierarchy to curiosity, it exposes how constrained our structures have become. When individuals with fluency and judgement can move faster than teams embedded in process, the issue is no longer talent. It is architecture.

This is why AI feels destabilising to large organisations. It bypasses the immune system. It allows work to happen without permission, revealing how much energy has been devoted to maintaining coherence rather than exploring possibilities.

The problem, then, may not be scale itself, but the confusion of scale with growth. Scale multiplies the same thing. Growth, in any meaningful sense, requires difference. It depends on variation, mutation and recombination.

Multiplication thrives on diversity. Scale smooths it away. In the last few months, Microsoft cut 15,000 jobs despite an 18% profit increase, Meta laid off 3,600 employees, calling AI a “mid-level engineer” and Google quietly eliminated roles across Android, Pixel, and Chrome. Salesforce cut customer support staff from 9,000 to 5,000 in under a year, with a 17% reduction in costs and performance reportedly steady or improved. I can sense the sterility increasing, masked by the joy of shotrt term savings.

When sterility increases, vitality does not disappear; it migrates to the edges, to small groups, to informal networks, to places where judgment still matters and failure is survivable. It appears in craft and practice, in people who take responsibility rather than wait for permission.

As we enter 2026, I am less interested in fixing large systems than in noticing where life is already reappearing despite them. The question is not how to make organisations more innovative in theory, but where meaningful work can still be done in practice.

Perhaps we have more choice than we think. Not in controlling the future, but in deciding where we place our energy. In maintaining systems that feel increasingly sterile, or in cultivating small, human-scale spaces where something alive can emerge and thrive.

I will begin 2026 focusing on these topics and incorporating my observations into my writing on The Athanor to identify ways to work with others to turn observation into orientation and orientation into action.

Because I suspect 2025 was only a mild introduction to the change we will have to accommodate, as we learn to dance with, rather than for, technology, and chart our own direction rather than follow blindly organisations that find themselves lost, confused and stuck without purpose other than short-term profit.

Onwards…..

On this last day of 2025, wishing you a smooth entry into 2026, and a fulfilling, satisfying and contented year.

I write in three places:

Here - about the potential power of craft in an automating world:

At Outside the Walls, about what I notice emerging outside the walls of convention and “best practice”:

And at The Athanor, on the power of conversations in small groups to bring about the change we want for ourselves.

I'm interested in the way that various strands of this are coming together. One of the areas that I'm playing with at the moment is how conversations themselves age as against the technology they beget. I mentioned in a previous post an idea of conversations ageing in line with alchemy, as follows:

1. Embedded Certainty (late Rubedo)

2. Anomalous Friction (Rubedo destabilising)

3. Private Disquiet (Nigredo, the quiet before)

4. Shared Naming (Albedo)

5. Reorientation (Citrinitas)

6. New Coherence (renewed Rubedo)

There's probably quite a nice little circular graphic here about going from the complacency of embedded certainty through the friction back to "born again" certainty.

The area that interests me most, though, is II, III, and IV. The emerging friction leading to private disquiet and into the shared naming. That I think is where the really constructive conversations take place, and where nothing that we've done before quite fits. We can learn from all of it, but every transition is slightly different, as you are saying here. The purpose of the conversations is less about finding agreement than finding constructive, incremental disagreement that informs and inspires.

Thanks for this, Richard. A timely reflection. I wanted to build on your “AI as personal transport” insight, and tweak a couple of details.

Venezuelan economist Carlota Perez became quite a sensation about 12 years ago among the vanguard of the Digital age, the people pushing big corporations to adopt agile ways, DevOps, and all that jazz because her model clearly spells the dangers of not being early to the Deployment period party.

Being an economist, she collected data covering the last 250 years to shed light on the dynamics of bubbles and golden ages, which is the subtitle of her major work: “Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital” (2002). She proposes 5 ages: Industrial (1771 - 1829), Steam / Railways (1829 - 1873), Steel / Heavy Engineering (1875 - 1918), Oil / Mass Production (1908 - 1974), Software / Digital (1971 - ?).

The average duration of the first 4 is 52 years. I’d like to propose 51 years for the last one, ending in 2022 with the release of ChatGPT. The age of Digital has been in the Deployment Period for a while, defined as that period after the bubble bursts (dot com) when Production Capital takes the lead, rather than Financial Capital.

Financial Capital is at the helm of the Age of AI, currently past the first bit of the Installation period ((Interruption) and well into the Frenzy. Once the bubble bursts (who knows when) and regulation comes in, then the Tech Titans hope to inherit the Deployment Period of this age as well as the last one. All previous incumbents dreamt the same dream. We’ll see.

Perez’ model is also good in that it recognises Capital as the engine, not Technology. In her interlocked 3 spheres of change, the technological loop provides the seed, the motivation for the Economic loop to unleash the frenzy leading to the bubble, and then through Production Capital to motivate the third loop (Institutional) to change mores and ways of working. Which sets the scene for the next season, etc.

That’s the first tweak: I don’t think that AI is part of the previous technological revolution, in the Perez sense.

I really like your statement about the possible future of organisations being “less like modern corporations and more like Guild 2.0”. One reason that I like it (perhaps perversely) is that it implies an ecology where Feudalism 2.0 is also present. I’m thinking of the current global crop of populist authoritarians making inroads everywhere alongside Musk, Karp, etc. To be clear: it’s not that I like feudalism, I mean that I like your statement because it points to a possible ecological necessity of that as a consequence of an environment that makes Guild 2.0 feasible. Which is fascinating to think about.

So, yes, to AI as personal transport, with ChatGPT as the Model T of the species. My tweak is that I view consumer-level AI as a hobby, such as amateur radio or generating your own electricity: not a world-changing actor except in freak circumstances.