I started the year with the idea of exploring ways to introduce artisanal thinking into our work and lives around three themes - craft itself, community, and confidence. That idea still holds, although what is becoming clear is that it will not behave in some neat, linear, reductive way. The three feel inseparable, each affecting the other, so I’m going to treat them like the grain in a piece of wood and go with the grain where it shows itself rather than just power over it for sake of sticking to a plan.

Looking back over this year’s posts, a shape seems to be emerging that I had not planned but which feels valuable, the recognition that craft is a form of rebellion against the tyranny of process thinking, scale and absolute efficiency: a small rebellion perhaps, but an important one.

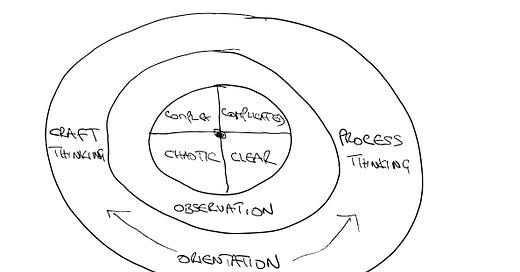

I often journal or doodle to help me think. I saw how I could link the approaches of two of my favourite thinkers, John Boyd and his OODA loop and Dave Snowden and his Cynefin model. I wanted to create something to hold the differences between the world of industrial thinking and capital efficiency we have been brought up in, and what I sense as the emerging world of systemic thinking and human potential. It’s just a doodle, but a start:

At the heart of it is Dave Snowden’s separation of the world of mass process on the right - the clear and the complicated, where efficient repetition is the best approach, and the complex and chaotic on the left, where exploration, trial and error, and experiential learning is required. Surrounding it is the observation part of Boyd’s loop; the ability to disengage ourselves from the system and see it for what it is and then re-engage with the orientation that gives us. (the models themselves can be seen in my previous post here)

I think the challenge for those of us who were brought up with the industrial mindset is not demonising it but recognising its boundaries. There are areas where it is absolutely the right approach, but it also leads to the inexorable logic of seeing technology in general and AI in particular as substitutes rather than tools for humans. The trick, such as it is, involves creating a semi-permeable boundary between process thinking and craft thinking and accessing the most useful of each for us.

The right-hand path takes us down the path of qualifications, resumés and the selling of ourselves as products or services, and the left-hand side down a path of creating something original that we sell. The right-hand side talks about careers and mass thought leadership and the left-hand side talks in the language of original thinking and discovery. The right-hand side is about efficiency; the left-hand side is about beauty.

The two sides are not incompatible. The challenge for the New Artisan is to avoid being carried away by the mimetic force of compliance to the thought leadership of industrial logic. If we are to achieve growth beyond the narrow confines of just “more” and the logic of Davos, then our individual, tiny rebellions in what we do and how we do it matter.

All very well, but how do we start thinking about this in a world where most of our jobs, mortgages, and colleagues are fully paid-up members of industrial logic?

At this point, I will go off-piste from craft to confidence for a moment (an appropriate metaphor, perhaps, when going off-piste at Davos is not possible due to lack of snowfall and reliance on artificially created snow - a form of perverse poetry). A couple of posts ago, I identified the framework being taken by those making the move out of employment into self-employment as craftspeople.

As I’ve continued watching them, a number of things have attracted my attention.

Firstly, it has become clear that one of the real challenges they face is how they value their work. Almost without exception, they price themselves compared to mass-produced alternatives of what they make in a craft version of imposter syndrome. Equally without exception, the mentors they are assigned introduce them to sponsors (galleries etc.) who achieve prices in several multiples of what they had originally thought.

Secondly, they undervalue their creative understanding of and relationship with the materials and tools they use. Their commercial leverage is in how they see what they create often as much as their ability to make it, It’s about more than design and more akin to the instincts of an artist - facilitating the emergence of what is important. Important as design is, I think it has become, like much of coaching, an industrialised function that loses connection with the spontaneous.

I’m not sure Picasso ever designed, but he was a genius at deconstruction.

Thirdly, with some, has been the confidence to accept the observations being made but rejecting the specific advice in favour of adapting it. It's a courageous move when faced with someone who has an established reputation and is recognised in their field, and therefore all the more heartening to see the reaction, the joy even, of those whose advice they have adapted when it all comes good, and there encouragement when it doesn’t. These are mentors who do not want to be copied.

I think there is much to be learned here for those who are not taking up the potter’s wheel or the lathe but rather aiming to introduce a sense of ourselves into our work. To make a mark on it. Kilroy was here. What I think of as “Deep Branding” that runs through everything we do, rather than purchased Branding Veneer that only touches the surface for a period of time.

It is tempting to put down an expert list of things to do here, but it would be nonsense. As Oscar Wilde said, “be yourself; everybody else is taken”.

Here though, are a few thoughts that occur to me:

A cute logo doesn’t make us stand out. It might be good to have when we’re famous, but until we are, it’s our work beyond the boundaries of what is expected that defines us. It’s our ability to be present with the client, whether that is a real person or somebody we have in mind. As artisans, our job is to create a connection between what the client says they want, what we create, and the unspoken needs of the client, distinctively and memorably.

Scale makes us remote. Scale is a core part of the dogma of the industrial model and almost an industry in itself, but carries with it a significant shadow. We can scale production easily enough, even if it carries with it increasing degrees of product and service homogeneity. Relationships - internally inside the business and externally with clients, in another matter altogether. As artisans, clients are buying connection with us, and Dunbar’s numbers are a good practical guide. We can have very good business relationships with a thousand fans, but once we start to get beyond that, we enter celebrity territory, and that’s a different relationship altogether.

Brands can be sold. Relationships cannot. Entrepreneurs thrive on spotting a gap, building a brand, selling the brand and moving on. Rinse and Repeat. Artisans are different because they find a niche and occupy it. Where entrepreneurs excel is at what James Carse called the “finite game” - bounded by rules, timescales, scores, winners and losers, artisans play the finite game - the game of keeping the game in play. Client relationships are a balance sheet asset item for Entrepreneurs; for Artisans, it’s part of their identity.

It’s not about us. Always a sobering thought, but it’s not us that matters to the client. We provide them with something that helps them see or become something they didn’t know they weren’t. Something that accesses thoughts and ideas way below the surface analytics of need. (I’ve become fairly allergic to the superficiality of HBR in recent years, though this from Michael Schrage is where this thought found its origin.)

Competition doesn’t really exist. It strikes me that, for the artisan, competition is very limited because what we provide is an amalgam of skill, attitude, and relationships. Competition only really exists in mass markets where direct comparisons can be made. Connecting with those who will value our work is a very exercise to the shotgun blast of social media. That’s a subject for another time.

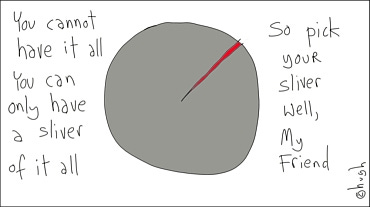

Finding our Sliver

It’s different for each of us. It depends on what we feel driven to do, how we present it and the resonance between what we provide and who we are. There are plenty of slivers out there, and they rarely compete with each other. We can make a satisfactory living as part of a fulfilled life.

I think there is a way we can approach finding our respective slivers in each others company. Too much now for this post - I’m already at the outer limits of word count, so it will have to wait for next week.

Until then, have a great weekend.

Resources

Finite and Infinite Games. James Carse. “An extraordinary book that will dramatically change the way you experience life. Finite games are the familiar contests of everyday life, the games we play in business and politics, in the bedroom and on the battlefield -- games with winners and losers, a beginning and an end. Infinite games are more mysterious -- and ultimately more rewarding. They are unscripted and unpredictable; they are the source of true freedom.”

Who Do You Want Your Customers to Become? According to MIT innovation expert and thought leader Michael Schrage, your strategic marketing and innovation efforts will fail if you aren't asking this question. In this latest HBR Single, Schrage provides a powerful new lens for getting more value out of innovation investment. He argues that asking customers to do something different doesn't go far enough-serious marketers and innovators must ask them to become something different instead.

Cynefin. Dave Snowden’s site and blog. Always worth reading.

John Boyd’s OODA loop. Chet Richard’s blog is a mine of information on all things Boyd. Fairly intense stuff, but a constant source of inspiration for me.

Upcoming

A combination of the break, and availability has made confirming a speaker this month challenging. I’ll open up Zoom anyway on Wednesday, 25th Jan at 18:00 UK time for those who want to catch up, and you never know; there may be a surprise….

First, love that Picasso bull panel! I'd not seen it before. All kinds of good uses I can imagine putting that to :)

Something about your post and/or the mood I read it in made me think of some great words from Tolkien as picked up by Steve Blank: "Not all who wander are lost." I feel as though some substantial part of my career I have been made to feel like I ought to apologize for being a wanderer, when it is precisely my wandering that makes my valuable.

Another thought from this week's wanderings comes from a chance encounter with Nick Cave who was asked what he thought about some lyrics spit out by ChatGPT "in the style of Nick Cave." Let's say, for openers, that Nick was not impressed. Read for yourself here https://www.theredhandfiles.com/chat-gpt-what-do-you-think/

As you suggest, the problem with mass production is not that it doesn't work, it's just not suited for everything. Likewise, people who think that ChatGPT came into existence to be a songwriter are probably barking up the wrong tree.

To the thought that craft is rebellion...I have great sympathy for this thought with the caveat that the object of rebellion is not always overthrow. Craft makes room for, keeps a place for, insists on the value of things "made by hand," things that bear the mark of their makers.

Having been in this space you describe for over a quarter century, the most unrelenting question is that of monetization. The solution is often a range of choices related to lifestyle, whether your art is your principal work or a side gig, and what does retirement look like. Part of the solution is building community in the communities where we live, where we support our neighbor’s artisan work.