Artisans, Asymmetry, and New Crafts

The Increasing Need for the Amateur...

This evening, at 5:00 pm UK, there will be an open Zoom call for New Artisans and those Outside the Walls. It will be our normal open session, with a starting theme of the sources of the information we use to shape the work we do.

There is something more than unsettling about observing different responses to the political, economic and geopolitical shocks we are experiencing now. Where did such a lack of resilience come from, and why are our responses so unimaginative and tepid? Why does a slight increase in Employers’ NI cause paroxysms of helplessness and blame? How have we arrived at a point where our business propositions are so fragile that the slightest puff of economic wind blows them over like shallow-rooted trees?

I think we have a problem with the culture of the “professional” (as against the Professions - that is a different story…). Those whose focus and rewards are on short-term performance measured mainly in money, rather than systemic health. They have little or no real “skin in the game”, are tenants not owners, and can walk away when things fail.

“Simply: if you can’t put your soul into something, give it up and leave that stuff to someone else.”

― Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life

From football managers, to business managers, to consultants and politicians we demand professionalism - an ability to produce “performance” on demand through whatever means. Whether that is greater extraction from what we already do, using privileged information to arbitrage resources, recycling what we already know through consultants’ shiny slide decks, and, when all else fails, getting rid of people who know what to do while those who don’t contemplate their navels and blame whatever is to hand, including, right now, our imagination of what AI might do.

Professionals are experts at creating the illusion of the Golden Geese that, given enough money, will keep on laying whilst ignoring the inevitability of the law of diminishing marginal returns. The evidence lies in exhausted sports stars, tired brands, the toxic selfishness of “drill, baby drill”, and managements devoid of imagination, commitment and courage avoiding anything that smacks of risk.

Frederick Winslow Taylor’s Scientific Management was published in 1911. At eighty-four pages, it concisely presented Taylor’s four principles of scientific management. These principles revolutionized industrial organization by emphasizing time-motion studies, task standardization, and managerial responsibility for workflow optimization. Carl Jung’s ideas, which became his “Red Book,” occurred between 1915 and 1930. B.F. Skinner’s work on behaviourism started in 1938, and Maslow's work began in 1938. Between them, they capture the essence of how we design the modern workplace.

I’m not sure we’ve had many original ideas about work since then. Rather, we prefer continually refining and regurgitating refinements on those original insights, allowing them to become dogma, promoted as answers by professionals.

Yet work, if not the workplace, has changed beyond recognition. We have turned much work into a mindless process, measured it to within an inch of its life, spread it around the globe to source it cheaply, and now we are outsourcing it to intelligent technology.

When offered the potential to reinvent work, we seem still trapped within organisations that want the equivalent of Henry Ford’s “faster horse.”

The cult of the Professional is in danger of draining our economy with an obsessive pursuit of profit and a lack of connection to craft or community. I suspect that no one who carries the label “professional” has created anything truly original in regard to the workplace in the last century.

Not so the Amateur. The clue is in the origin of the name; it is from the Latin amator, ‘lover’, from amare, ‘to love’. Closely linked to vocation, vocare, a calling. The things we value result from love, are shaped by artisans and commercialised by entrepreneurs until driven to commercial exhaustion by professionals.

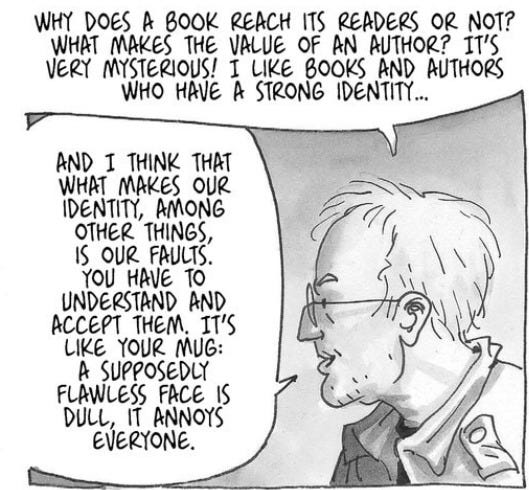

Amateurs go where professionals fear to tread and embrace ideas because they cannot do otherwise, not because there’s profit to be had. The thought was captured for me by Steve Done, an amateur in the most glorious sense of the word. He persuaded me to read a graphic novel - something I have never been inclined to do. The subject matter is a partnership between the owner of a vineyard and a graphic artist. It is wonderful. There is something about the graphics that convey more than words can. It requires a different approach to reading, and to be read as a physical object (being a sceptic, I got it on Kindle, but have now corrected that). There is a fantastic line in it that I like:

I think that captures the essence of the difference between amateur and professional. For a professional, faults are to be eliminated; for an amateur, they must be harnessed.

When AI is becoming very professional, we need amateurs.

I like to go back to find the “first growth” of ideas before they hit the mainstream and become professionalized and sanitised. I wondered where the first thoughts about our tendency to imitate entered the social sciences, and it took me to Gabriel Tarde’s “Laws of Imitation” (1890). He posited that:

…social life is primarily driven by imitation rather than conflict or economic forces. His theory is built on three fundamental laws:

1. The Law of Close Contact – People are most likely to imitate those they are closest to, such as family, friends, and local community members. Proximity plays a key role in shaping behaviours and beliefs.

2. The Law of Superiors over Inferiors – Imitation tends to flow from those perceived as superior (e.g., elites, role models, or authority figures) to those seen as inferior. Social status influences what and whom people choose to emulate.

3. The Law of Insertion (or Adaptation) – New ideas and innovations do not emerge in isolation; they build on pre-existing ones. When a novel concept is introduced, it is either adopted and adapted or rejected based on how well it fits existing social structures.

Gabriel Tardé. Laws of Imitation

What interested me was not the revelation but where it came from and the opposition and scepticism he faced for what we now consider obvious. Tardé was an amateur, a Lawyer by training and a sociologist (before we coined the term) by conviction. His work laid the foundation for later developments in sociology and social psychology, influencing figures such as Émile Durkheim and contemporary scholars of network theory and diffusion of innovations.

I want to know where those figures are today as we wrestle with the implications of what we have created with AI. My instincts are to keep them out of the hands of professionals whose instincts will be to build faster, cheaper horses competing on familiar race tracks.

I am currently running an experiment. I’m taking real and created business challenges and running them through a series of AI filters - first, an interrogation of assumptions using DeepSeek R1 and now Chat GPT with advanced reasoning, and then a series of steps to bring about a company and sector-specific strategy. My intent is to consider what is missing that matters, not from a “professional” standpoint (the output is good and, with a few hours of work, would more than pass for a standard consultant offering) but from an “amateur” one.

I want to notice what is missing because that is where the artisans' asymmetric influence has its greatest effect—in shaping and articulating what is needed to enable the emergent to do so. Where the insight of artisans can affect operational leverage points, such as client relationships, information effects, where artisans curate and source information and contacts outside the mainstream that carry insight and originality, being influence multipliers, reaching the parts that mass media and production do not and perhaps most of all, network effects, the essential elements of tipping points. In all three areas, heart and soul outweigh logic and cost in the early stages, setting the scene for what comes next and giving serendipity a chance.

These things are not reducible to logic. They harness other qualities—excitement (Latin excitable, "rouse, call out, summon forth, produce"), enthusiasm (entheos, "divinely inspired, possessed by a god"), and a deep connection. These forces enable us to shape the materials we choose to exercise the vocation we sense.

For a while, perhaps only a couple of decades, artisans will have the asymmetric power of insurgents. These are the foundation of new crafts, I think. They will facilitate the creative and generative use of new technologies , rather than merely their exploitation.

Yes, these skills will eventually be supplanted by the technologies they shape, as artisans always have been—but not before they have shaped the future.

See you this evening, 5:00 pm UK…

When I started my consulting practice thirty years ago, one of the first things I observed was the inability of people/leaders to be able to see how the structure of the organization affected everything else. People were subject to structure. In effect, function followed form. The transactional nature of relationships developed. There was a consequent loss in the ability to think clearly, which affected the agency of people to take initiative to do human things like solve problems and communicate broadly. Everything became scripted and permission based.

One of the responses to this highly structured organizational environment was the emergence of a culture of entrepreneurship. Ideas, relationships, initiative, focus on impact are all present in a start-up. Then, as the business grows, founders turn over the business to managers who scale the business or set it up for acquisition. Entrepreneurism is not a sustainable organizational structure.

As I saw these three patterns of behavior related to ideas, relationships, and structure, I also saw the unsustainability of this situation long-term. What I saw three decades ago is coming to pass. We have entered a time of transition that has no clear end point. It means we all, as amateur sleuths, be vigilant in observing what we see that works, and elevate its importance for awareness. We also recognize what doesn’t and must change.

It means this transition is not like leaving home to go on a trip, only to return back to the same home. Instead it is a reorientation of our perception of what is real, and how to adapt to it. Not a new house, but a new world. So, we identify as amateurs learning what we need to know minute to minute.