Assistant, or Doppelganger?

The importance of not forgetting what we understand that technology doesn't

Something is compelling about this week’s turmoil around AI. Following last week’s “Stargate” $500 billion glitz with all the tech bros, a small Chinese business produces something nearly as good using some old milk bottle tops, a piece of string and some spare Tesco vouchers. It makes a great story, and when money is made out of stories, and its timing was (|intentionally, I suspect) perfect. Cue much wailing and gnashing of teeth.

What amazes me most is that we are surprised.

In the meantime, I think we’re missing the point. While everybody gets animated about size, speed, and cost and dreams of what the tech might do, we seem to be less focused on what it already does than on what it might do.

AI is different. It is not like, say, the early days of spreadsheets, when we were amazed by the capability as they gradually gathered more and more features, most of which the majority of us never use. Spreadsheets do the same thing at increasing levels of sophistication, and although they may be fast and thorough, they only do what we could do without them, if more slowly (and if we can’t, we shouldn’t be using them)

AI has acquired a seductive whiff of magic. Not only will it process for us, it will find stuff for us and suggest things. If we prime it correctly, it will even write like us. AI is not just a tool; it is a doppelganger.

The idea of the doppelganger asks profound questions about identity, consciousness, and the nature of self. One of its best-known instances is that of Catherine the Great, who allegedly saw her doppelganger sitting on her throne, prompting her guards to shoot at it. That feels resonant right now. AI is less a tool, and more an emerging relationship, and I think we have an adoption problem.

“I'll be more enthusiastic about encouraging thinking outside the box when there's evidence of any thinking going on inside it.”

Terry Pratchett

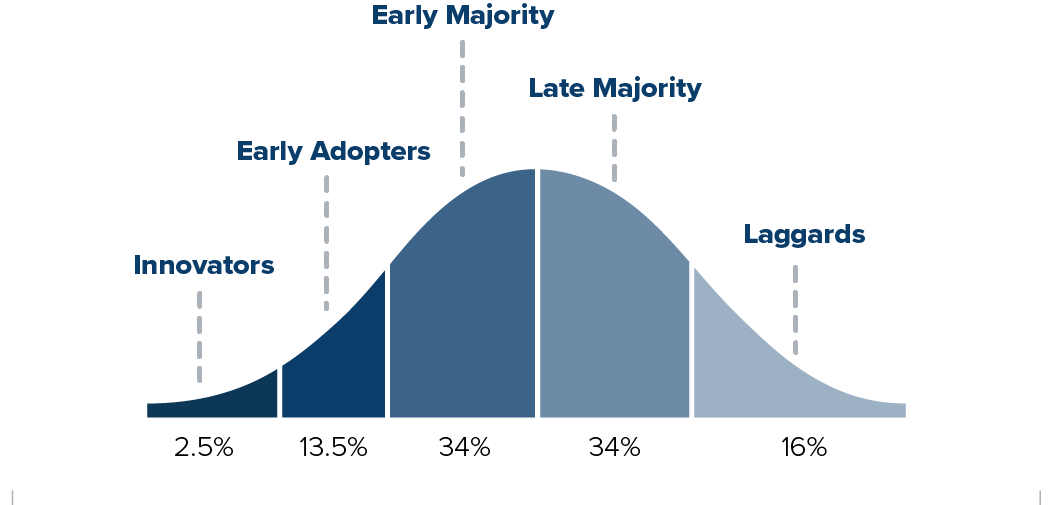

I often find the Rogers curve a useful mental model. It shows the idea of innovators and early adopters and the chasm between them and the early majority. Again, AI is different. It is more about developing a relationship, getting to know our Doppelganger, and forming a partnership rather than acquiring a passive tool.

It is, I suspect, a challenging relationship, and reminds me of Iain McGilchrist’s story, taken from Nietzsche:

A wise master rules a domain and appoints a trusted emissary to carry out his orders and manage the land on his behalf. The emissary, initially loyal and efficient, grows increasingly ambitious and begins to believe that his success and authority are his own achievements. Over time, he undermines the master, seeking to take control of the entire domain. However, lacking the master’s wisdom and broader understanding, the emissary leads the realm into decline.

It interests me how meekly people use AI in areas where they cede authorship to their doppelganger, whether writing an email, updating their resumé on LinkedIn, or even writing an article. We are delegating our identity. It might only be a routine email, but how long will it be before we cede more and more and encourage the doppelganger emissary to move into our seats?

I am an enthusiast for AI, even as I am wary of it. As a research assistant, or a “sparring partner” it is immensely valuable as long as I remember that what ever goes out under my name is, to the people receiving it, who I am.

Whatever I adopt shapes my future. Whatever we adopt as a group, a team, or an organisation determines who we become. The enduring appeal of doppelganger stories stems from their ability to tap into our universal human fears about identity, death, and the uncanny—the simultaneously familiar and strange. They challenge our sense of uniqueness and raise unsettling questions about what makes us who we are.

I wonder what the Doppelganger doesn’t know that we have forgotten we know? In our rush towards efficiency, productivity and short-term “performance”, do we lose sight of the essence of what we provide?

The other side of that coin is our hubris and the stories we like to tell ourselves about our superiority until one morning, somebody turns up doing what we do, having improvised from the abilities we have made available but have not cared for or valued.

“What, I have kept asking myself, is all of this duplication doing to us? How is it steering what we pay attention to and—more critically—what we neglect?”

Doppelganger: A Trip Into the Mirror World. Naomi Klein

In our rush to delegate to technology what we know how to do, we must allow space, as individuals and communities, for questioning and respecting why we do it.

Time may be short.

Onwards!

Two thoughts.

1. What does not get discussed is that new technology's adoption is rarely at the level of sophistication that the new technology promises. I don't want to say that most of us are mediocre technologists, but we use technology to the degree that we need it. We are efficient users. We may try things but discover that it adds a burden of responsibility that we are not prepared to adopt.

Richard, you have clearly shown me that AI has value. The questions central to my work are not technical or analytical. So, in almost everything else I've done, I will continue to be an outlier.

2. Roger's innovation adoption curve was developed almost 50 years ago. I don't think I have ever seen any research on how quickly adopted innovations are abandoned. If adoption is the front door, what does the backdoor look like? I wonder how many organizations have flirted with AI and determined that it isn't for them. By the end of the decade, we'll have a better idea.

"sparring partner" - that's how to use the LLMs. Don't 'think' for me but question my thinking, and challenge my ideas.