Developing a craft environment

Creating a space for New Artisans

In last week’s post, I considered how we might think and act to bring out the craft in our work. This week, I want to extend that further to reflect on what we do and where we do it. Just as we become the average of the five people we most associate with, so I think we are shaped by our physical environments and the simplicity and economy of our approach to what we do.

(note: I’m now putting useful references at the end of the post, rather as embedded hyperlinks; I think they distract from the narrative. Let me know if you think differently or if there is a more considerate way I might reference that works better for you)

On Wednesday evening’s Zoom call, there was a point where there was a felt sense of difference in how we use the word “craft” - as a noun, or verb. The difference between what we do as a craft and crafting what we do. It was only a moment, but it changed the direction of the conversation, so I’m going to start there and see where it takes me.

What follows is more a stream of thought than some statement of truth, and my intent is to provoke companion thoughts as we aim to convert ideas into aspects of personal practice.

Crafting has a more comprehensive feel than Craft; something active about it suggests wider involvement in what is around us, an inferential aspect that suggests a direction of travel, whereas Craft feels somehow more static. If Craft focuses on skill, Crafting focuses on attitude.

“We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.”

Winston Churchill. October 28, 1943

I think it is difficult to produce beautiful work in sterile surroundings. Those who take what they do seriously pay attention to where they work. One of the places that have always impressed me is the pre-schools of Reggio Emelia, where the children are involved with the architects to design the places where they will learn and play. The end result shows in teachers, children and community.

It seems in such stark contrast to the places we build based on criteria of financial return, from our offices to hotels and the endless plains of production line “Executive Houses”, as though people are commodities to be packaged as efficiently and cheaply as possible. The Schools at Reggio also use the language of the artisan - classrooms are Ateliers, and teachers are Pedagogistas - and evoke a sense of craft and philosophy in teaching children in a deprived area of Italy.

In our conversation, we discussed the idea of holding the client as we would turn a piece of wood, noticing and using grain, flaws and other unique characteristics to produce something that united function and form. I can imagine applying this to almost anything we do, as long as those crafting the product or service are directly in touch with the person it is being crafted for and paying for it.

I think this has important implications. There is a point I suggest where, when businesses scale, the connections between those producing what is bought and those buying it, get disintermediated by the machinery of the bureaucracy needed to manage the complexity of the organisation. It asks the question of whether a large organisation can accommodate those who want to craft what they provide. We can pay lip service to it through agile approaches, although I think that optimises connections within a process more than the connection between creator and end purchaser. This opens a series of questions around organisational design that are too big to go into here but may well warrant a separate discussion at another time.

Another aspect of a craft environment is the psychological as well as the physical environment, and there is much current discussion on creating “psychologically safe” environments for people to feel secure. However, I think an artisanal space has to go a step further into what Martin Knox described in one of our discussions as a “brave space” - a place where the heretical and novel can be entertained with the client. That, in turn, suggests another feature of artisanal work, a determination only to work with those who respect your work.

All of this seems designed to make life difficult for a standard organisation and demand levels of dialogue and collaboration within the supply chain that is difficult to meet. I think that may well be the case and is perhaps the price to be paid in order to do the work we are prepared to sign.

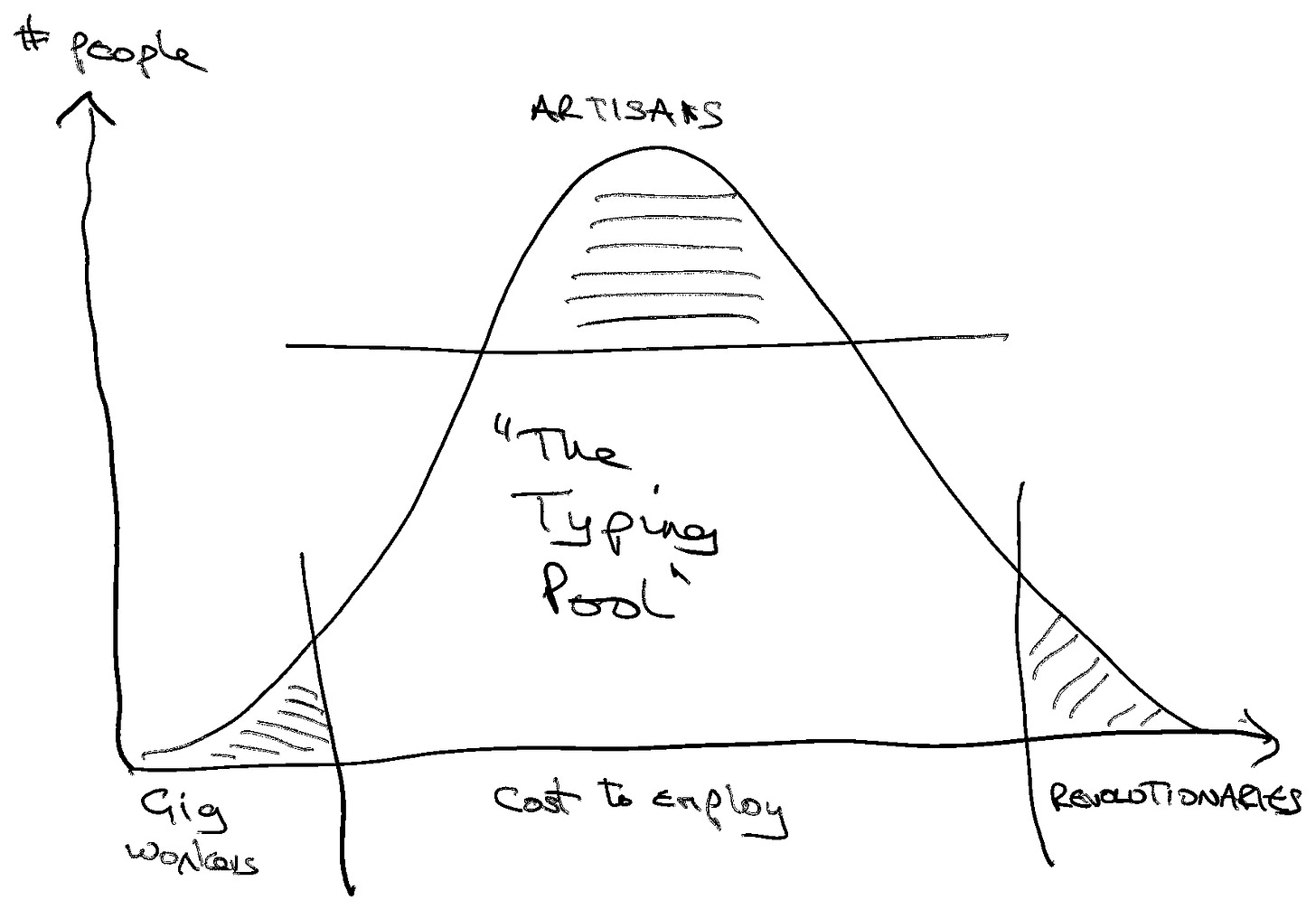

During the week, on my Reflections blog, I posted a doodle that featured a mention of artisans, so I’ll repeat it here in a different context and hope those who have already seen it will bear with me.

I was riffing on an idea of a latter-day “typing pool”, where thoughts were turned into communication by those uninvolved with the dialogue, and suggested a parallel with many of today’s organisations.

I was floating the idea that three types of people disproportionately impact organisations facing the changes we are. Firstly, the “gig” workers who deliver front-line routine service; secondly, the artisans who design and shape that service; and lastly, the revolutionaries who understand the system and radically reinvent it. The Gig workers are good at what they do, and highly mobile. The artisans are those who work directly with the client to craft what is created, and the revolutionaries rethink and bring about disruptive change that delivers what the client wants in entirely different ways.

Take an area not normally associated with artisans, Accountancy. I have seen it in this way; the gig workers are the skilled and qualified accountants who do the numbers, then the artisans who do the work of understanding the soul, not just the mechanics of the client business to ensure that they can present the numbers in a way that informs what is important to the spirit of the business, and lastly, revolutionaries, like Xero, who rethink the entire process around an idea of beauty.(See reference below)

Those outside these categories are exposed to the increasing capabilities of technology, as initial insights into the emerging, unexpected capabilities of AI make clear.

As we get into 2023, I’m increasingly confident that our work together is starting to uncover an element of business that adds a different dimension to the normal product/price/place/promotion of conventional marketing. It is not something that can be “applied” or, I think, “designed” because it comes from a different place - the ethos of the organisation.

Perhaps that fifth “P” is “Presence”, the distinguishing characteristic of the artisan?

It raises at least as many questions as answers:

Is it possible to make an existing business artisanal, or do we have to start at the beginning?

How is an artisanal business designed?

How big can an artisanal business become?

What are the implications of leading an artisanal business?

What are the correct metrics for measuring “performance”?

I’ll post further thoughts as they occur during the week, and we can engage with ideas in the chat. I sense although there’s still a long way to go with this, some of the questions we ask will take us to actions that can make the artisinal personally, and commercially, valuable in a way that enriches our lives.

Next week, I’m going to turn my attention to how we develop the confidence in ourselves and other to move away from conventionand take steps towards becoming more artisinal.

Coming Up

I’m still finalising a speaker for this month, and am putting Weds 25th in the Diary. I’ll keep you updated directly.

Have a great weekend!