I’ve long been fascinated by Japanese approaches to craft in what they do. From Martial Arts, through Calligraphy and Poetry to the Toyota Seisan Höshiki or “Toyota Production System”, they combine a focus and attention to detail with a context that sees whatever they are making as part of something much larger.

The terminology has a poetry to it - Jidoka (automation with a human touch), Mura (unevenness), and Muri (overburden) have a different ring to the more brutal terminology of Scientific Management. The disciplines extend to how one can take something broken and make it more beautiful by repairing it, acknowledging its history whilst adding to its present.

We need to learn from that.

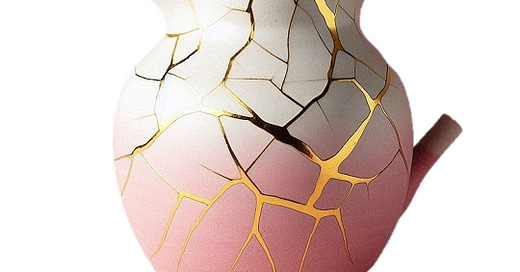

I love the mindset of Kintsugi - the art of repairing ceramics with gold lacquer and its relative, Yobitsugi, where new pieces are created from the broken parts of others. Then there is Sashiko, the art of repairing textiles by making the repairs beautiful, not invisible. Underpinning them all are crafts with their own language of methodologies and materials.

The idea resonates strongly for me on this “Liberation Day”. I’m writing this the day before and will be posting before we know the details, as the idea of breaking things to see what happens pervades our Western world.

Plenty of other people are commenting on the economic and social absurdity that a noisy cohort driven by shallow business thinking and greed is imposing not just on the world but on most of those in a nation we trusted and whose people we admired, so I will not add to that.

We don’t want what is being lost back, corrupted as it has become by a dark form of capitalism. The pieces are sound - people, technology, and trade - but the structure of privateers and pirates, individuals and corporates whose unbounded greed and sense of entitlement has given us the problems of planetary and social depletion we now face.

What inspires me more is how we use the pieces of what is being broken to create something more beautiful.

The repairs made by these Japanese crafts rely on two main qualities - the eye and skill of the crafter and the lacquer or thread used to create the transformation.

We’re a bit stuck. Organisations desperate for the stability that enables them to continue the current absurdities display a stunning lack of imagination, craft and courage to change how they operate.

They are classic examples of the “Shirky Principle”

The Shirky Principle, coined by Clay Shirky, suggests that institutions or entities tend to preserve the problems they are designed to solve. They focus on “certainty and stability”, self-preservation, and exploitation in preference to exploration.

One of the tragedies of this lack of imagination is that organisations are destroying the ingredients of the lacquer they need to repair what is breaking. They are displacing people in favour of technology, and the damage they cause themselves puts even the medium term beyond reach.

Putting pieces back together is much easier than putting relationships back together, as shared in a wonderfully constructively angry post yesterday by

on his “decrapify work” blog that captured the energy of the situation we face well.The lacquer that consists of the people who make work that matters happen is, of course, not destroyed, just displaced. I’ve written before about the nature of New Artisans as catalysts for what replaces what is failing, and it is equally true today.

Somewhere along the way, hubris has convinced countries and organisations that they are somehow indispensable and “too big to fail”. They are not. Like the USA and other developed economies, these organisations exist on an ocean of debt funded by the stories they tell. The minute those stories fail to convince, the oceans get drained, and the baby leaves with the water in which it has been bathing. It will be instructive to see how much of whatever happens due to “Liberation Day” sees the plug being slowly pulled.

But where does the lacquer go?

We’ve long recognised that organisations exist through the efforts of a nucleus of talent in different disciplines, supported by much administrative overhead, constrained by management and ignored by shareholders.

These nuclei become more critical as technology erodes administrative overhead, routine management and “bullshit jobs”. For most of these nuclei, money is only part of the game. The work they do is part of who they are. Money is a poor measure of real value.

Management obsessed with measuring has few cards to play as they respond to shareholder howls. They offer more money to those who already have enough of it but not enough of what matters beyond money - creating what matters: community, purpose, and leadership.

Reality: organisations have no right to loyalty; they have to earn it and their current thrashing about is destroying it.

What I notice from my small corner of the world makes me smile. Those being displaced continue to connect outside the organisation in groups that offer support, share insights, generate ideas and solidify relationships. They are the seeds of what comes next.

They remind me of Rönin - Masterless Samurai committed to an ethic and seeking somewhere to exercise it.

These people are the lacquer.

There are organisations, normally small and medium-sized, founder-led and delightfully free of feudal shareholders, where these ethics are to be found.

Where they don’t, as these new groups form, they may just create their own.

Lacquer flows to where it is needed.

Kintsugi has three primary methodologies. The “Crack Method”, where pieces are joined with minimal delicate lines of golden adhesive, emphasising the cracks rather than hiding them.

Then, there is “Makienaoshi”, which involves replacing missing fragments with gold lacquer, effectively transforming the missing parts into gold, creating a seamless blend of original and repaired sections and finally, the “Joint Method”, where two broken items are brought together to form a new one reflecting the best of their previous forms.

It works well as a metaphor for what is happening to our organisations. The importance of “lacquer” is central to it. Without it, broken pieces are just broken pieces. With it, they are vibrant new entities with a whole new life ahead of them.

As the world changes around us, and the current mania for breaking things continues, we need somewhere to keep the lacquer. Somewhere for those who view wealth as more than money and for whom work is an expression of who they are to gather, learn together and find places to create something new from the pieces of the broken.

To contribute to this, we have created a container outside the walls of the frantic world of best practice, efficiency and productivity: a “Mighty Network” where New Artisans can gather to look at the world around us, find the pieces which create the new, and work together to help each other do it.

We have been meeting monthly, but with effect from today, we will meet weekly. There is no charge, but there is an intention.

To build a network of ideas and people to change how we think about work, in order to make life better for individuals, families and communities.

If you’d like to join us, drop me a line, and we’ll talk.

I love the idea of Kintsugi which celebrates the visible marks of an object’s journey, turning imperfections into unique elements of its story. This goes counter to the dominant narrative of our times; brainwashed by glib advertising bombarding our senses through every media outlet, perfection equals beauty has propelled the consumerist theme of masking imperfections.

Similarly, in the human quest for betterment we have striven for perfection as proof of competence, which is practically a bridge too far and can be the undoing of common people trying to achieve it.

In my book, YOGAi: Interplays of Yoga and Artificial Intelligence, I wrote about the value of imperfect.

"New Delhi’s Janpath market is thronging with tourists looking for traditional art and craft, where shoppers seek more than just gifts or souvenirs; they desire everyday items imbued with authenticity. Despite the prevalence of mass-produced goods flooding the market, there remains a demand for non-standardised, hand-crafted products. Surprisingly, the allure of imperfect indigenous crafts persists, as they evoke an emotional connection to the human touch and the richness of tradition.

Dreamweaving, often associated with dreamcatchers, originated in Native American cultures, particularly among the Ojibwe (Chippewa) people. In some traditions, imperfections in dreamweaving are deliberately incorporated as a symbolic representation of the imperfect nature of existence. These imperfections may include intentional gaps in the weaving or asymmetrical patterns, which are believed to disrupt the flow of negative energy and prevent it from entering the dreamcatcher’s realm. By acknowledging and embracing imperfections, individuals aim to create a balance that protects against malevolent forces while inviting positive energy and harmony.

Additionally, imperfections in dreamweaving may serve as a reminder of the impermanence and vulnerability of life. By accepting and embracing imperfections, individuals cultivate humility and resilience, which are believed to strengthen their spiritual defences against negative influences like the evil eye. In this sense, imperfections in dreamweaving are not seen as flaws but rather as integral elements of the protective and spiritual symbolism associated with dreamcatchers."