Hypotheses

A time for alchemy

This month's posts have been circling something important: we're becoming dangerously comfortable with outsourcing our thinking. Whether to other people, to prevailing opinion, or increasingly, to AI.

I write about what I notice as a means of thinking in public, and then periodically review it to see what patterns emerge. So far this month, I've written about mediocrity and the danger of relying on assistance (whether from others or AI) to avoid thinking critically and instead going with the flow of those around us. That took me to "The company we keep", both human and other. Jim Rohn said that we become the average of the five people we surround ourselves with, and I think the same principle applies to what we read, watch, and the conversations we have. In turn, that led me to explore boundaries, whether we're operating within them, outside them, or on the cusp.

These posts took me to what's on my mind this week. Two posts in particular resonated. The first was in The Economist, concerning the inherent insecurity of AI. The essence of the article (£) is that AI’s most significant weakness lies in the same feature that makes it so powerful: its willingness to follow plain-English instructions. Because large language models don’t distinguish between data and commands, they can be tricked into carrying out hidden instructions buried in documents or online content. When you combine three things- exposure to outside data, access to private information, and the ability to communicate externally, you create what experts call the “lethal trifecta”. That mix makes systems inherently insecure, regardless of the amount of training or patching that is done.

And if that’s true for machines, it holds for us too. When we hand over judgment on things we haven’t read or don’t really understand, we’re just as open to hidden traps. The risk isn’t only technical, it’s in our own willingness to outsource thinking.

Another article, found in Semafor, concerning the decline in American Thinking caught my attention. It’s not fair to pick on America - I think any economy obsessed with speed, efficiency, and productivity fits the same bill, and I found it resonated strongly with the Economist article.

The real threat of AI may not be the loss of jobs but the steady decline of our ability to think for ourselves. Just as muscles only grow through time under tension, our minds strengthen when we sit with difficult texts, test conflicting ideas, and struggle to put them into words. Reading and writing are not side activities; they are exercises that build deep thought, much like squats build strength. Yet AI short-cuts tempt us to skip this workout, outsourcing essays and summaries, and in doing so, we risk hollowing out our own capacity to understand. Research already shows that literacy is falling and attention spans are shrinking, with many students leaving school without the stamina to read a book or craft an argument. Add to this the “lethal trifecta” of AI insecurity, systems that can be tricked when we ask them to analyse material we haven’t read or don’t understand, and the danger becomes clear. The machines may not take our jobs, but we could end up surrendering the very skills that make us human.

It begins to feel like efficiency, productivity, and the need for speed are a drug we willingly consume. Instead of coming off the drug, we look for bigger and bigger doses through apps and technology and surrender to it things that should not be surrendered to it. I find AI to be an outstanding technology, but somewhere along the line, it has become so hyped to meet financial expectations that we have created a culture that has little regard for the collateral damage it may cause.

I think our response to it exacerbates it. There are some excellent articles, opinion pieces, and research on the current state of AI, but they share a common thread. It is commentary without action. Observation without meaningful orientation. It feels a little like the automatic pilot in a plane that is about to hit the ground as it shouts. “Pull up, Pull up”. The pilots are so accustomed to the autopilot that they've forgotten how to fly manually.

The article on the decline in American thinking posits a provocation that we only have 18 months to remedy this. The article's timeline is alarmist, but it does form a hypothesis, and if there is one thing we're short of right now, it's hypotheses.

Hypotheses are designed to be wrong. The benefit of them comes in the discipline of finding out why and learning from it. We can't navigate when we're standing still, and the benefit of a hypothesis is that it forces us to move our thinking. If we find we are wrong, that's great. It means we need to change direction. Finding out we're wrong is infinitely preferable to worrying that we're wrong. What we need now are spaces where we can be wrong together, where hypothesis-testing becomes a collective practice.

We need Lunatics.

The Lunar Society of 18th-century Birmingham was less an institution than a circle of restless minds who met by moonlight to share experiments, failures and ideas. Nicknamed “lunatics” for their habit of gathering under the full moon, they made open exchange their modus operandi: scientists, engineers, entrepreneurs and reformers testing and stretching one another’s thinking. They worked across boundaries, treating commerce and science as partners rather than rivals, with curiosity as their common ethic. The benefits were immense, ranging from steam engines and ceramics to advances in chemistry and medicine, but their more profound legacy lay in showing how a small, self-organised group of so-called lunatics could spark an age-defining transformation. The spirit of those lunatics found expression even in art. Joseph Wright of Derby painted alchemists discovering phosphorus instead of the Philosopher's Stone, capturing the exact moment when old certainties gave way to new elements. We're at a similar hinge point now.

On my bookshelf, I have a copy of Marshall Goldsmith’s “What Got You Here Won’t Get You There”. If a book can look at you reprovingly, that is what it is doing. (James Clear wrote a great summary of the book.)

It is time to take action and develop and test my own hypotheses.

A Change in Rhythm

Since the pandemic, here and Outside the Walls, I've written close to 1500 posts. Each one has been a dot of sorts, either an observation or a sense of orientation, and quite often both. It feels like it's time to separate them. Observation is vital if we are to make sense of our current situation, but on its own, it doesn't accomplish much. Orientation is a precursor to action, and that's what I want to create more space for. To occupy, in however small a way, a similar space to the Lunar Society.

I will focus both New Artisans and Outside the Walls on observation, the raw material of orientation, and create a new space, The Athanor, for those who want to move from orientation to action. Posts will be shorter and more frequent as food for thought that aims to provide the raw material for something more tangible.

At the beginning of October, I will create The Athanor as a space to practice hypothesis-making, deep reading, and collaborative sense-making through monthly challenges, peer review, and structured experiments in thinking.

Introducing the Athanor

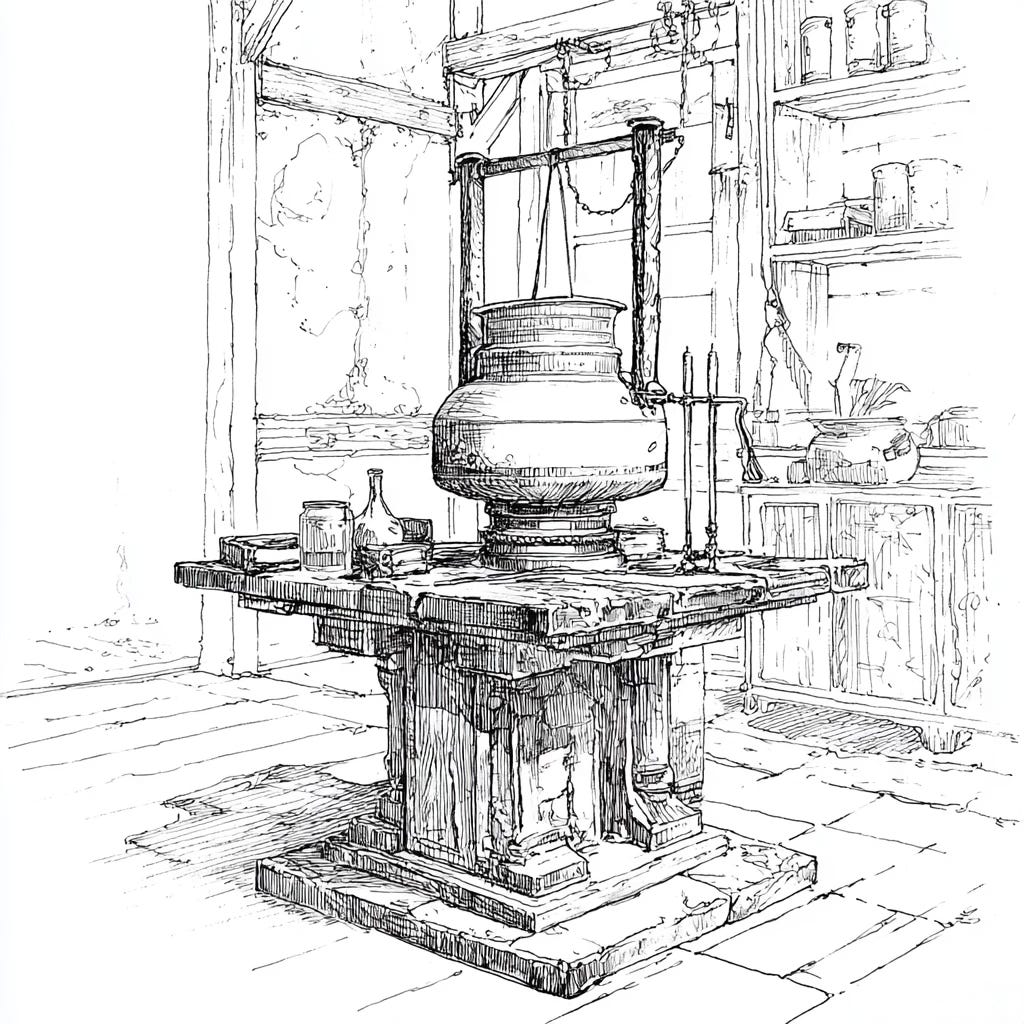

The athanor, the furnace of the alchemists, was never about speed or spectacle. It was built to hold a steady flame, a quiet fire that could burn for weeks without faltering. In it, substances softened, mingled, and slowly became something new. For the alchemist, the athanor was as much a mirror of the soul as a piece of equipment: a reminder that true transformation comes not from flashes of brilliance but from constancy, patience, and faith in unseen processes.

The athanor sits on the boundary between what is disappearing and what is emerging. It is a temporary, yet necessary space where new artisans can create hypotheses and develop their best work, away from the demands of scale and efficiency.