Move Slow and Make Things

Improvisation is a tactic, not a strategy.

There is a weird fascination and compulsion in observing people who don’t know what they are doing, apeing those who. It is evident in the mismatch between language and action.

“Move fast and break things” (MFABT) is a valid approach in a moribund sector. Evoking the spirit of Schumpeter’s creative destruction can work, provided you have enough financial and creative resources. However, when an industry is already hyperactive, it is akin to a child’s tantrum—breaking things to get attention, hoping somebody will take note and give you what you want.

And when the things being broken are people and communities, those instigating an MFABT approach are better regarded as hooligans, not heroes. Thoughtless, self-centred, sociopathic behaviour from those with more than enough resources and too little empathy.

As the hooligans lay waste, forcing return-to-office strategies, and hyper-monitored activity to develop working cultures that would have been the envy of those building the Pyramids, the palette of talent that exists in any creative enterprise turns from bright, vibrant colours to mushy brown. The things being broken do not deliver, the palette gets thrown away, and a new palette of colours is ordered in the hope that doing the same thing will yield a different result.

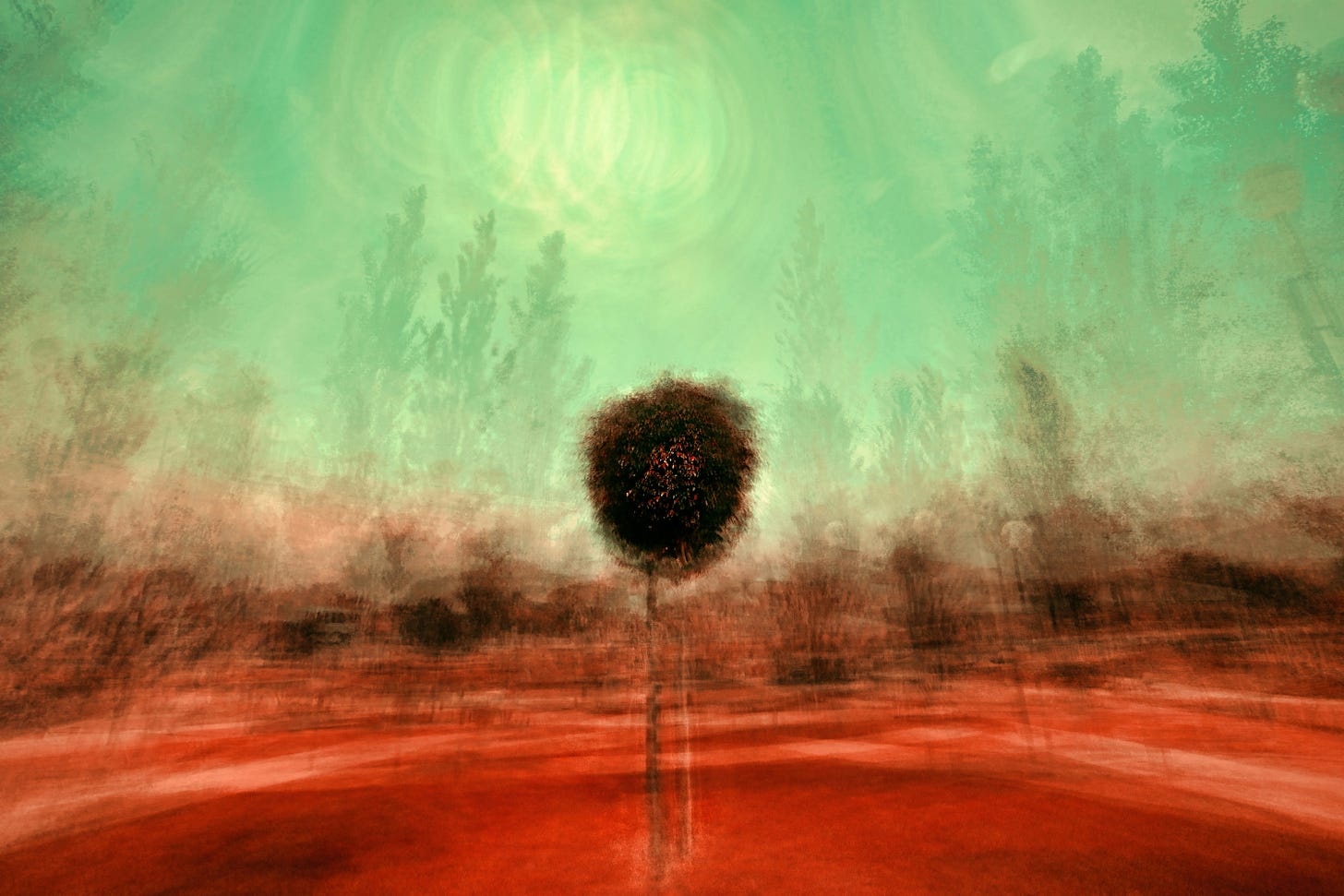

If the market is the canvas, and artisans the oil paints, we need to find organisations that are artists, not paint-by-numbers algorithms.

They do exist, in their thousands. You’ve probably never heard of them, but they exist. They need artisans. And where they don’t exist, we can create them. Those offering tiny original works of art created with love rather than mass-produced, shit-textured products driven by data.

What is missing is a way for artisans to find each other, share views and ideas in generous conversations, and point each other towards organisations that are artists—or create them from scratch.

When the emerging school of Impressionist painters emerged in Paris in the 1860s, driven by Monet, Renoir, Pissarro and Sisley, they could not exhibit in the Paris Salon, as their work was judged “not proper art”. (the term impressionist” was coined from a critical article on Monet’s “Impression. Sunrise”).

They met at the Café Guerbois in Montmartre, where they attracted other no-hopers like Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Paul Cézanne, Frédéric Bazille, Henri Fantin-Latour, Émile Zola, Louis Edmond Duranty, Alexis, Baudelaire, and Mallarmé. They mainly met on Friday evenings, and discussions were often lively and heated, with a "perpetual clash of opinions" that helped artists form their ideas. History suggests they did rather well.

Our large organisations remind me of the Paris Salon. We need a latter-day Café Guerbois.

I hope we can start here.

Moving fast and breaking things created temporary mediocrity.

Moving slowly and making things creates beauty.

“Moving fast and breaking things created temporary mediocrity.

Moving slowly and making things creates beauty.”

Including people!

It seems we rush children, too.

2 year old kindergarten,

Tryouts for 2nd grade basketball teams,

Harried parents running from full workdays to scheduled night time activities.

It’s no wonder the whole world seems edgy and clings to the promises of leaders who want more, faster.

As Simon and Garfunkel sang, slow down you move too fast.

A great interview:

https://youtu.be/Bi6NFPhsGyM?si=fiGj4luJes6xluW_

Thank you for your posts Richard.

They offer hope and possibility.

The pressure to monetize by commodifying the art as merch is constant. Relationship building is a more solid ground. You describe the Parisian Impressionists. At the same time, there were scientists, philosophers, and artists gathering in Viennese cafes to discuss their work and the context of their lives. Right now where I live, I am hanging out, almost daily, in a coffee shop that is intentionally designed as a third place (first place is home; second place work; third place, a social gathering spot). Groups gather daily for conversation. Fridays and Saturdays are game nights serving good German beer. New relationships formed where none would happened. The investment in time is not for marketing, but rather for perspective and support. I had a lovely conversation with a Vietnamese grad student the other night. She asked if I came there often. I said, "All the time. See you soon." Relationships are not a utility for marketing. They are a means for marketing. As I am constantly saying to people that i meet, "Who do you know that you think I should know, and would you introduce us?" Relationships mean so much more, if we allow them to form organically.