Postcard from the Edge

Artisans as Lichen. Something about Transformation

It can be so easy to fall into a way of thinking. After a while, what starts as an exploratory hypothesis evolves into a convenient truth that changes how we see things, and before we know it, what has been a useful temporary construct has taken up residence and resists eviction.

My own antidote to the decay of curiosity is the company I keep, both human and literary. Relationships with people and work that offer different angles on things I am exploring and from whom challenge and criticism are expected and welcome. Creative friction with trusted friends is a powerful force.

As I’ve been exploring the idea of New Artisans, an underlying assumption has developed that, somehow, artisans and organisations are a difficult mix. The assumption that the freedom and agency artisans need to do their best work is a rare commodity in organisations that are measured in terms of productivity, efficiency and metronomic increases in profit.

That assumption was serendipitously challenged as I was “tidying my bookshelves” (I was actually putting away the huge pile of books cascading onto the floor off my desk, coffee table and other flat surfaces). As I picked up my copy of Merlin Sheldrake’s “Entangled Life,” it was open on page 80, and a line caught my eye:

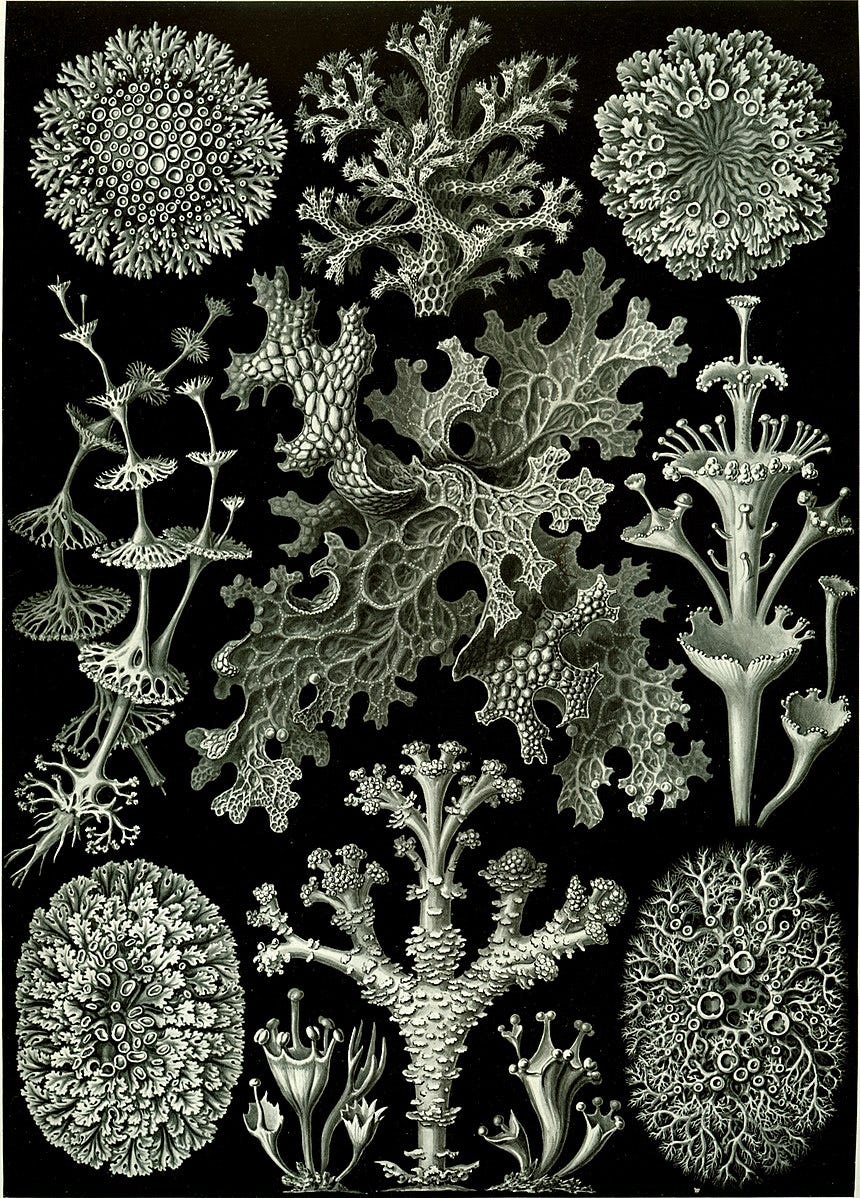

…the Swiss botanist Simon Schwendener published a paper advancing “the dual hypothesis of lichens”. In it, he presented the radical notion that lichens were not a single organism, as had long been assumed. Instead he argued that they were composed of two quite different entities, a fungus and an alga…the lichen fungus offered physical protection and acquired nutrients for itself and the algal cells. The algal partner harvested light and carbon dioxide to make sugars that provided energy…

The idea kicked up a storm, with most suggesting that one had to be parasitic on the other and that mutual cooperation was not possible. Fast forward around one hundred and fifty years and lichens are becoming stars in their own right. We still do not fully understand but recognise them as having powerful, unique properties and an ability to survive extremes of environment few others can match (exposed on the outside of spacecraft to full-on exposure to cosmic radiation, they appear to get out of their deckchairs and settle in..)

So, I have an open question about the assumptions formed about incompatible artisans and organisations. Could we develop something altogether more like lichen, where artisans are recognised for their ability to turn ideas into value, not as “talent”, something to be acquired like prize livestock, but as autonomous entities, and organisations could leverage their ability to attract investment and turn value into money without having to succumb to the desire to control everything within their reach?

It’s a very big ask, but as technology automates the mundanity that is the administration of most organisations, could we bring the creativity of artisans closer to the conversion power of organisations?

It would require radical thinking and an acceptance that our ability to survive lies not in trade alone, but in the capability to make things worth trading.

This is worth pursuing, Richard, but we may need to find some new lenses to do so. For example, this quote from Jane Hirshfield reframes the juxtaposition between science and poetry:

'Poetry and science are allies, not opposites.

Both are instruments of discovery,

and together they make the two feet of one walking.'

—Jane Hirshfield 🌿