Tech is an engine with nowhere to go. Artisans are Navigators.

AI is not the challenge. Our Organisations are.

“For every truth, there is an equal and opposite great truth” Niels Bohr

There’s a point at which we can no longer join the dots we have to hand.

We mix, compress, heat, and freeze them, and still, they will not join.

That is how I feel right now about our relationship with AI.

I had a “Millicent Moment”

Every morning Millicent ventured farther into the woods. At first she stayed near light, the edge where bushes grew, where her way back appeared in glimpses among dark trunks behind her. Then, by further paths or openings where giant pines had fallen, she explored ever deeper into the dim interior until one day she stood under a great dome under columns, the heart of the forest and new. Lost. She hid and achieved a mysterious world where any direction would yield only surprise. From "The Day Millicent Found the World". William Stafford

When we’re lost, it doesn’t matter which direction we go in as long as we move.

I have spent a month experimenting with different AI, reading about it, trying to establish a relationship with it, and I’ve done enough work to realise I’m lost. Any direction I take will yield only surprise, not clarity. AI might be a new religion where great mysteries and potential truths get wrapped up in dogma in order that we can deal with it.

And, of course, it creates a great market for those new priests who claim to understand it and offer us absolution. At a price. Indulgences to keep us out of technohell.

There is a freedom to being lost and a power to the necessary self-sufficiency it demands. There is no one to follow, only fellow travellers to be found.

AI is not the problem. The organisations we built for a different time are.

They are old, and tired. They do not want to take risks, they want guaranteed returns from what they understand and are run by those who are machine operators more than entrepreneurs. When it comes to innovation, they want the equivalent of Henry Ford’s “Faster Horse”.

This is a problem because AI is a game changer, even in its current form. It asks us why we work for an organisation when more and more of what it provides us by way of getting work done can be done by AI. It feels like worrying about the candle market when you’ve just been given mains electricity.

Every General Purpose Technology (GPT) follows a similar path. From the wheel and axle and writing over five thousand years ago, through the steam engine and electricity, to computers and the internet, General Purpose Technologies usually start as clever solutions to specific problems, quickly spreading as people find new uses. Soon, they reshape everyday life, changing how we work, live, and interact, until they become normalised and regulated, ready for the next big thing to come along.

AI is the next big thing, and whilst the hubris of our big organisations encourages them to think they can control and integrate it, they can’t.

I find it interesting that every GPT seems to have followed a similar path to the one we are using to describe the progress of AI.

It is invented by someone who can see what others cannot, with the mind of an artist. It makes its presence known through artisans, who make the idea tangible. We use it in our service, like the technology centaur - half human, half technology but still directed by the human. After a while, human and technology merge to become a cyborg as we cannot separate ourselves and the technology and it becomes integrated into how we work, until, it becomes, like our current organisations, so well established that we become servants of it, measured in utilitarian terms. We have a “reverse centaur”, now with the technology, or the organisation, in charge.

And then what happens. I wondered. It turns out that there is no antonym for “artist”, no “reverse artist”. we can identify roles for those who obey rules over expression - censors, efficiency experts, or the “philistine patron” who support art only where it flatters their ego - but there is no archetype. So I explored ideas from literature, to find characters who filled this role to see what it might teach me.

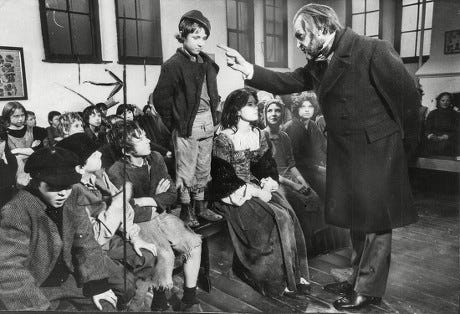

Then came the Thomas Gradgrind moment.

You will remember him from Charles Dicken’s “Great Expectations” as the stern headmaster and businessman of Coketown in Charles Dickens's "Hard Times," and the embodiment of Victorian utilitarian philosophy, famously declaring, "Now, what I want is Facts... Facts alone are wanted in life." Raised on rigid principles himself, he establishes a school where imagination is squashed and children are treated as pitchers to be filled with facts rather than minds to be nurtured. He applies this same cold logic to raising his own children, Louisa and Tom, with disastrous results—his daughter enters a loveless marriage and his son becomes a thief. The subsequent unravelling of his family forces Gradgrind to confront the bankruptcy of his philosophy, leading to his redemption as he gradually recognizes the essential value of human emotion, imagination, and compassion. By the novel's end, Dickens transforms this once unyielding figure into a humbled man who abandons his "eminently practical" worldview to embrace the "wisdom of the Heart," making him one of literature's most compelling examples of moral evolution and the triumph of humanity over mechanistic thinking.

I think this might be where we are. As we are able, with increasing confidence, to delegate much of the routine of the STEM skills we have been so encouraged to learn to AI, where do we go to play the part of human? To revel and harness what we do that is beyond logic and reason. The space that, nearly a century ago, Kurt Gödel described when he proved that mathematics is not decidable. He proved that there are statements in mathematics, which are true but not provable within the system.

Algorithms have their limits. Within those limits, they are hugely powerful, and we haven’t found those limits yet - but they are there. When we do, the next stage of our development will be driven by artists and artisans.

There will be a point where the TechBros have their Gradgrind moment, but until then, we have to remember that relying on them, or their products, is a high risk venture.

Humans are artists at heart. Artisans are Navigators. AI is a tool for Artisans.

There are a number of Navigators forming small groups to explore and realise ideas of what it means to be humans in an age of AI at Outside the Walls, so we’ve created a small, closed Mighty Network to see how we might work together. If the idea interests you, and if you would like to join or create your own small group, drop me a line.

We’re doing it because we think it needs doing, not to make money.

In the last century, the landscape of scientific inquiry was reshaped by groundbreaking discoveries that challenged the notion of complete objectivity. Gödel’s incompleteness theorems, Einstein’s relativity theories, and Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle all injected elements of subjectivity and human interpretation into the traditionally precise realms of mathematics and theoretical physics. These revelations suggested that the human element, with its inherent vagueness and subjectivity, could not be ignored in the pursuit of understanding the universe.

The following from Rebecca Goldstein’s book, Incompleteness, elucidates the Achilles heel of scientific objectivism:

"Gödel’s incompleteness theorems. Einstein’s relativity theories. Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. The very names are tantalizingly suggestive, seeming to inject the softer human element into the hard sciences, seeming, even, to suggest that the human element prevails over those severely precise systems, mathematics and theoretical physics, smudging them over with our very own vagueness and subjectivity. The embrace of subjectivity over objectivity—of the “nothing-is-but-thinking-makes-it-so” or “man-is-the-measure-of-all-things” modes of reasoning—is a decided, even dominant, strain of thought in the twentieth-century’s intellectual and cultural life. The work of Gödel and Einstein—acknowledged by all as revolutionary and dubbed with those suggestive names—is commonly grouped, together with Heisenberg's uncertainty principle, as among the most compelling reasons modern thought has given us to reject the 'myth of objectivity'."

By dint of coincidence, incompleteness, relativity and uncertainty are the very words used by Vedic philosophers to describe Māyā, or the illusion of reality, and these are discoveries of physics in the twentieth century. Just as Vedic philosophers grappled with the limitations of human perception and understanding, modern scientists encountered unsolvable contradictions and paradoxes when probing the depths of the cosmos. These revelations served as a poignant reminder of the inherent limits of knowledge and the ever-present influence of subjectivity in our quest for understanding.