The Boundaries of Ambition.

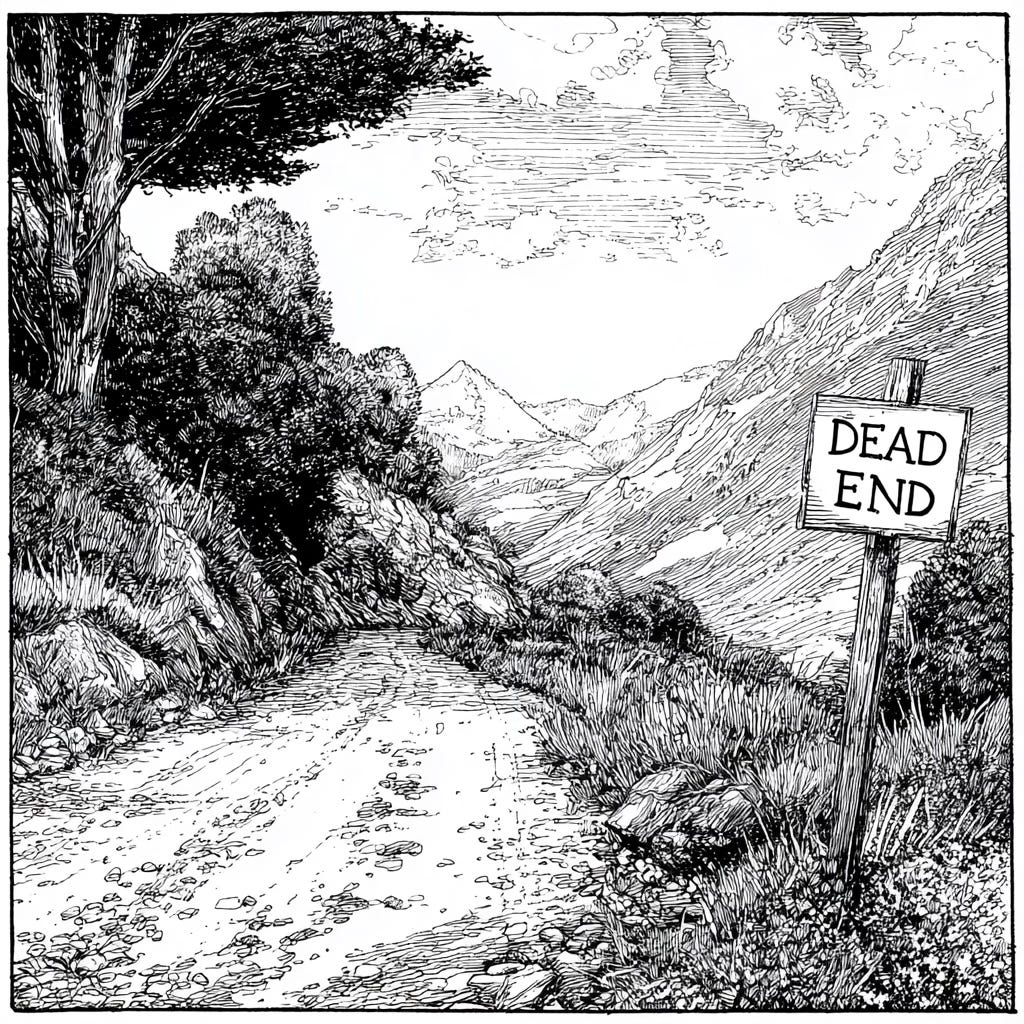

choosing the signs to ignore

“The mindwall has become so entrenched in our heads that it remains unchallenged and unquestioned.”

― Nick Hayes, The Book of Trespass: Crossing the Lines that Divide Us

The political events we have witnessed this week bear the familiar hallmarks of a short-term response to a long-term problem. Although framed in the language of geopolitical doctrine, the thinking behind them is as recognisable in organisations at our current stage of industrialisation as it is in international politics.

In complex environments, doctrine offers an illusion of certainty that masks a sterility of thinking. Under pressure, what is presented as adaptive strategy is often constrained by the unspoken theatre of doctrinal assumptions. These assumptions are rarely articulated, let alone examined. They shape what feels sensible. What appears risky, is sanitised or dismissed before it is properly considered.

Doctrines do not collapse so much as decay, and only rarely are they revived. What begins as a clear boundary, designed to reduce uncertainty at a particular point in time, is gradually stretched by new actors, shifting incentives, and changing conditions. Principle gives way to precedent, legitimacy to compliance, and a guiding signal becomes background noise.

Where boundaries endure, it is not because they are asserted more forcefully, but because they are re-established through contemporary consent, embedded in institutions and practices, and permitted to evolve. Where this does not happen, doctrines persist as defensive habit rather than guidance, quietly constraining adaptation while giving the illusion of order.

This matters for New Artisans because it is easy to become trapped within organisations shaped by old ways of thinking and insulated from the ideas that are shaping the emerging future. We may become highly competent in what is slowly becoming obsolete, while struggling to remain attuned to what now matters. Expertise, under these conditions, can become a liability.

There is a common assumption that doctrine is enduring and rigid, while strategy is adaptive and ephemeral. In the military, doctrine is typically revised every five to seven years, with deeper transformations occurring over much longer cycles. Corporate strategy, by contrast, often operates on much shorter horizons, sometimes three years or less. The irony is that, while strategy appears more fluid, unspoken doctrine is often taken for granted. Strategy changes, but always within the same invisible boundaries.

In organisations, hidden doctrine becomes strategy’s invisible prison. Comfort with past success reinforces existing routines and competencies, leaving little space to explore new ones. Over time, layers of unquestioned assumptions build up about what works and what does not. A kind of doctrinal sediment forms. Organisations become trapped not only by their capabilities, but by the stories they tell themselves about those capabilities. It is reminiscent of technical debt, where systems continue to function while carrying architectural decisions from a very different era.

Nothing is actively broken, but change becomes increasingly difficult.

This hidden doctrine amplifies several forms of myopia. Competitive myopia limits attention to familiar rivals while missing disruption from outside the field. Temporal myopia elevates quarterly performance over longer-term resilience, and most insidious of all is learning myopia. Knowledge that does not fit existing mental models is quietly rejected, not because it is wrong, but because it is uncomfortable.

There is, at least, an underlying honesty to military doctrine. It is explicit, written down, debated, and periodically revised. Corporate doctrine is rarely afforded the same visibility. It exists, but remains largely unspoken. In this sense, it resembles what Pierre Bourdieu described as habitus: the internalised dispositions that shape perception and action without the need for explicit rules.

The result is elaborate strategy theatre. We rehearse change, innovation, and transformation, but always on the same stage, with the same actors, the same production crew, and the same backstage staff. The performance changes. The structure does not.

The challenge for us as artisans is that we, too, can be shaped by this habitus. We become the average of the people, ideas, and constraints that surround us. The ideas that might invigorate our thinking are never seriously entertained. Many of them would fail, of course, but some would not. Yet the landscapes we might explore are marked with an implicit sign warning us not to proceed.

“Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch’intrate,”

“Abandon Hope, all ye who enter here.”

The inscription above the gates of Hell in Canto II. “Inferno. Alighieri Dante

Perhaps, as new artisans, we need to recover the nomad within us. Not as rootlessness, but as the ability to carry our home with us rather than defending fixed territories. Our strength lies less in walls and more in mobility, adaptation, and the patient acquisition of deep knowledge about changing landscapes.

That raises a final question. If deep knowledge of changing landscapes cannot be acquired inside organisations constrained by invisible doctrine, how are we to develop it? And where are the spaces in which this learning can take place?

Those are questions for my next post.

In the meantime, the Wednesday group will be meeting this evening at 5 o’clock UK time on Zoom. You would be very welcome. One of the quieter truths we will explore is that developing deep knowledge often requires working together, outside the walls of organisations, in places where doctrine can be named, questioned, and, where necessary, left behind.