The Wayfinding Artisan

A year of wandering, wondering and making do.

I have always appreciated the period between the winter solstice and New Year. It’s something of a rite of passage for me, a natural time of reflection as work recedes, family gathers, we pass the point of the shortest day, another birthday, and move towards a new beginning.

I enjoy looking back at posts I have written in the year and looking for clues as to where the idea of New Artisans might be heading. With so much going on, it can often be a challenge to find a place to start that isn’t just a rerun of the year but rather something more catalytic that brings things together. Something, though, always appears from somewhere, and this year, right on cue, was a wonderful article in the Economist on Polynesian navigators (paywall, I’m afraid) that provides a great metaphor for where I feel I am with this.

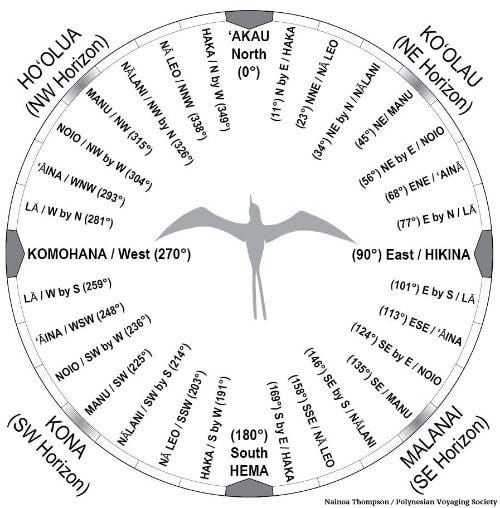

Long before Europeans found their way there, Polynesians with no written language, maps, compasses or other technology were navigating their way across vast distances with great accuracy. Although much remains unknown, what little we do know paints a picture. They relied on forms of “backcasting” - navigating forwards by looking backwards, developing a deep understanding of the stars, wave and swell patterns, bird and sea creature behaviours, and even noticing the green reflection in clouds of stands of palm trees. Using these individually and in combination, they developed a visceral relationship with their surroundings that “brought the islands to them” rather than the more assertive idea of going to the islands. It makes for an elegant, poetic image.

It also provided me with the thread on which to pull to bring together this year’s writing:

Abstraction.

It is in the nature of the artisan to develop an intimate, visceral relationship with the nature of their work. Whether it is the texture of slip, the typeface of an article, making their own paint, the fit of a joint, spending time over a sequence of words, or the presentation of a set of accounts, the character and soul of the artisan are expressed in their work. Creating something of that depth demands the inefficiency of a willingness to rework, revisit, or start over in order to do the work we are prepared to present. It is not about perfection but about always being a little better in a constant search for something we’re often not sure of but know is there.

To succeed economically, in our currently accepted sense of the word, makes that more than difficult. Our worship of scale, the search for unicorns, and the pressure for constant, regular, reliable growth make the idea of a pause, or fast before feast, unacceptable. Constant feast is the order of the day.

Every time we follow a process, use an app, a template or outsource, we are abstracting away our connection with what we provide. We lose that sense of touch, texture and connection in order to provide precise replication, increased speed, reduced costs, and increased profits - often for people we do not know.

Apparently, apprentice Polynesian navigators were required to spend hours on their backs in the water, learning the nature of the swell in the water and the signal it offered. You may not be able to see the island over the horizon, but the change in the swell it creates by its presence is detectable by those who know how to sense it.

Every time we label something, create a shortcut, or automate, we lose touch with what we are working with. Famously, London Cabbies who have passed “the knowledge” have a bigger hippocampus than those who rely on satnav. They have spent, on average, three years on scooters absorbing the sights, smells, sounds and nature of the city, as well as its layout, in a way technology cannot hope to do or arguably needs to do in order to fulfil its basic function. With the intention to have driverless cars on the road by 2026, we are in sight of taking the abstraction one stage further, and doing without the driver. AI threatens to do the same elsewhere, even if, as yet, the threat is only a story.

The problem with abstraction is that we forget what has been abstracted, and the skills atrophy. We become wilfully blind. With a bit of practice, I could still use a sextant, tide tables, star maps and the other paraphernalia of old technology navigation, and I can still read an ordnance survey map. Even that, though, is a real abstraction compared to those ancient Polynesians.

Given the rewards of automation and efficiency, the temptation to abstract away the inconvenient and challenging is huge, but what we abstract matters. It doesn’t go away, and like legacy software, we build on top of it until we cannot see it any more, but we cannot eliminate it. Accretion is easy; decrement is not. If we do not retain an intimacy with that which we allow to be abstracted, we will not notice the gaps that appear until it becomes too late.

When the power runs out, a GPS is no more than a poor doorstop.

Abstraction removes signal.

While the pressure is huge, and the temptation to let technology, business model templates, and consultants make our lives temporarily easier so that we can produce more is high, abstraction is still a choice we consciously make but which the artisan in us resists. The artisan in us creates spaces to stay in touch with the sources of what we create. Artisans deliberately pause and linger when something doesn’t feel right rather than apply more technological force. They allow their creativity to “lie fallow” in order to recover and regenerate.

What abstraction removes is the signal of “weak connections”. It is the equivalent, perhaps, of the swell of the sea for those Polynesian mariners and, to borrow another metaphor, the creative mycelium that is the basis for artisanal collaboration and conversation. Efficiency asks us to focus on today; whilst we’re doing that, the noise masks tomorrow creeping up on us. Noticing the small things, the unusual, and making time to play with them together is the raw material of tomorrow’s success. When things are uncertain, planning is often a placebo. Preparation, on the other hand, is wisdom.

The likelihood that any efficient organisation will be ready for the unexpected is low. It is why there is such a market for mergers and acquisitions, as large corporations turn to organisational botox to recover their lost youth. They are often unsuccessful, as study after study demonstrates because they have abstracted away the relationships they need to integrate the new successfully.

2024. A Year of Making Do.

Who knows where this coming year will take us? We find ourselves overwhelmed by the hype curve of artificial intelligence, apprehensive in a sea of geopolitical uncertainty, and facing huge economic volatility as we contemplate elections in areas where democracy is under serious threat from populism.

In the coming months, many organisations may find that the cultures they have created as a result of what they have abstracted away in pursuit of efficiency mean they lack the resilience to respond to the pressures they will face.

Making Do will become an art form.

The new or different is not something to anticipate passively like next season’s shoes. Better it be conjured up from the conditions of the present, from what is already here and now. Surrendering to one’s circumstances does not mean giving in to the inevitable but rather to yield to the possibilities that each specific situation brings, learning to be resourceful with what is at hand. Reinvention is the practice of breaking down the familiar into a molten state to redirect its flow, affecting a change in perception. New economies emerge based on indeterminate principles of asymmetric exchange: theft and piracy, gift giving and donation, the art of losing one thing and finding something else. Lending should be treated with some caution however, for whilst it suggests generosity it often expects more back in return. To “make do” is not to manage with less nor hope for more, rather a call towards a life of creative action over dutiful consumption - an instruction to begin making and doing.

The Yes of the No. Emma Cocker. P13.

This is an interesting proposition for the artisan who is connected not just to their own sense of craft, but to others with a similar sense of theirs because they are the raw material of what comes next. As we have covered in this blog, artisans provide the starter culture that creates the conditions for major phase changes, from ancient times to the industrial revolution.

As we enter the unknown of artificial intelligence, now is no different.

Going into a New Year, my thoughts are gathering around how we prepare for the changes we will see but cannot plan for, so that when we find ourselves surprised, we are prepared and confident. Independent enough in skills and confident enough in character to develop interdependence with those we choose with whom we can exercise all our capabilities, not just a small subset.

In my year-end review of my weekly Reflections, I wrote about New Artisans living “outside the walls” of conventional organisations. There are others- from regenerative farmers to those in the circular economy who all share characteristics and the potential to support each other.

In the coming year, I intend to build bridges to connect them, individually and in small groups, and see what happens.

Lovely musings Richard, my lived experience has often been similar. As always the big question remains for me at least, how do we manage financially as artisans, especially if we have not succumbed previously to the rules of the games for making money. Many of us have been making do for years. We may be flourishing in other ways and grateful for those. But in the midst of the entangled big things you mention, our financial resilience is more fragile than ever.

Best wishes to all for a healthy, fruitful start to 2024.

We reflect on the past and anticipate the future, but can only ever be where we are right now. I'm personally indulging a growing sense of purposeful direction while consciously looking down to see where my feet are right now and trying to appreciated their rootedness. On good days this builds a compelling creative tension, on bad days it creates anxiety - it's a continual negotiation.

Thanks for your excellent writing and all the best for 2024.