Weekly Journal

Artisans, and the Overton Window...

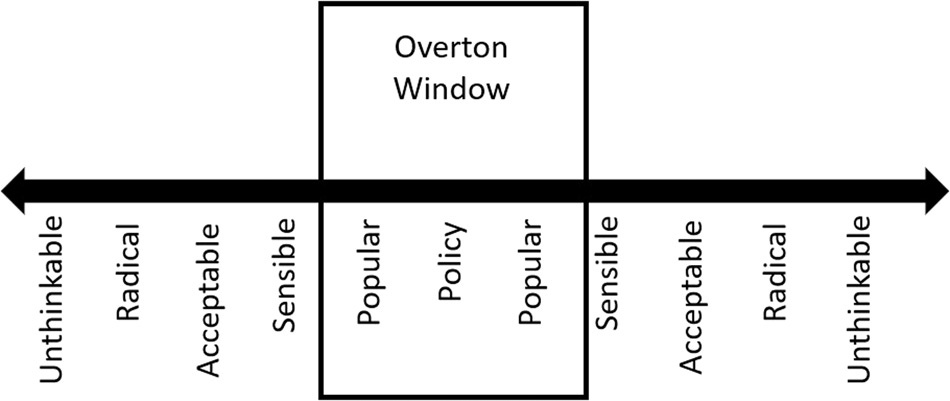

The Overton Window is a model used by politicians (and others) to consider what needs to be done to “move the window” - to make the radical and unthinkable plausible.

There is a point when we are waking up, in the shower, or out for a walk when an idea floats into our attention, and we cannot help but grab it and take a look at it. So it was with the Overton Window, a concept I read about years ago, when I was thinking about our relationship with work in general, and our employers in particular, and how it has come to be that we let people we don’t know, appointed by other people we don’t know, with agendas we have had no say in, have such a big say in the way we live our lives. How have we become this domesticated? What has moved the Overton Window such that we accept our lives being shaped by data more than relationships?

I think the question matters because we seem to be on the cusp of those decisions that affect our lives being heavily influenced or even made by artificial intelligence. I am, on reflection, an advocate for AI; I think that properly fed, well-supervised and widely accessible, it has the possibility to do a lot of the process heavy lifting for which we currently pay clever people a fortune, from finance to medicine and law, and free those minds up to do the work of solving big problems rather than just excavating current wealth in six minute billable increments.

Of course, therein lies the challenge. The temptation is to get AI to do the work to make our lives easier rather than freeing us up to do challenging work, further embedding inequality of access to capabilities and opportunities that will improve lives.

I thought about the jobs I have done and how they might have changed had AI been available; it was not a comfortable exercise. It was unsettling to think about how much time was spent in mimetic pursuit of “best practice” models and processes and how little was spent properly understanding those who worked for me, bought what we created, or sat in the supply chain. How little time was spent in second-order thinking about what might happen beyond the immediate intention of the action? We had lots of data (in relative terms) which we spent time poring over, even though the best it could do was give us generalities for which we created labels, but in doing so, abstracted their reality - and their humanity. We created a convenient distance that insulated us from them. We did, though, do what was asked of us, running what we were given charge of and, most of the time, returning more back than we were given.

Then, given the magic wand that all coaches are given when they qualify, I imagined how it might have been different if I had access to the sort of AI we are now developing. I could have let it do the detailed analysis and monitoring that we needed to do in order to report and budget (which I hated) much better than we did (and with far fewer people), as well as do the research and spot anomalies and trends in data. That would free me up to do the things I loved doing, talking to those who used what we created to find out how it affected them, and doing the soft, personal data gathering that AI cannot. Then, I would have the polarities from which insight springs. On the one hand, the numbers, and on the other, the sensory data and the opportunity to hold them in the same space and consider what was emerging.

One of the truths of leadership, especially in times of uncertainty, is that people don’t follow because of what we know or what we can do; they follow because of how they feel about themselves in our company.

We move their personal “Overton Window.”

As artisans, at this time, what matters is what AI cannot replace in what we do. We need to surrender to it what it can do gracefully and make sure we are in place and have the autonomy to do what it cannot.

I wonder, where might they take us, the new freedoms opened by AI? And, do we have capacity?